By the time I took the Principles of Reactive Programming course on Coursera last spring, I was already a fan of Scala and concurrent programming, so it was no big surprise that I fell in love with the actor model the moment I heard about it during the course. I’ve been wanting to write about it ever since, but have only recently had the time to actually do it.

Let this be the first in a series of articles where I explore the actor model; what it is, how it works, where it can help, and how some of its use-cases may be implemented. I’ll first describe what the actor model is and how Akka implements it, then move on to simple examples like hot-or-cold games, and finally end up in client/server applications such as multiplayer card or tile games.

Disclaimer: This post assumes that you’re at least somewhat familiar with Scala.

History and Definition #

The actor model is a concurrency model based on a number of principles first designed by Carl Hewitt et al. and published in 1973 under an article named “ A Universal Modular ACTOR Formalism for Artificial Intelligence”. It relies on individual processing units that can communicate with the oustide world (including other actors) through asynchronous messaging, and was perhaps first implemented commercially by Ericsson in the late 80’s as the basis of the concurrent programming language Erlang. The model has recently gained a mainstream attention thanks to the rising popularity of Scala and Akka, and the ever-increasing need for more concurrent programs.

The fundamental building block of the actor model, actor, is a computational entity that has a state that’s completely sealed off from the outside world, a behaviour that it change at will, some kind of address that other actors can use to send messages to, and a mailbox to store those messages (along with addresses to their senders), in the same order as they arrive.

Actors are hierarchical, meaning that they can form parent-child relationships. This helps model the domain more easily and allows for a more fault-tolerant application by propagating errors upwards or downwards the hierarchy to shut down the whole system or the failing actor itself (therefore granting high availability out-of-the-box), depending on the severity of the failure. Also, even in the event of such a parent-child relationship, the internal state of each individual actor is completely hidden from each other, so there’s a fair amount of encapsulation involved.

These qualities make it almost too obvious that they’re modeled after us, the people. We know each other by name, we only share what we choose to (even with our parents or children), we communicate with each other by talking (and don’t necessarily have to wait idly until the other answers), and can form some kind of hierarchy (having children, becoming managers or leaders, etc.).

What makes actors so great at working concurrently is that while they send and receive messages asynchronously, they process them one by one, without losing their order. This ensures that the reads from and writes to their internal states are always sequential (assuming, of course, a proper care is taken for asynchronous state I/O) and in order, so the integrity of the state is always intact.

Actors vs “Traditional” Programming #

The way an actor keeps its internal state completely hidden is that it doesn’t have any public field, property or methods (since they’re potentially compromising). Even the actor instance itself is unreachable, otherwise the encapsulation rule would be broken, since different instances of a certain class would have access to each others’ fields or properties, even if they were private.

For that reason, everything about an actor is private and hidden from others but their own, and some kind of address or reference that acts as their messaging gateways. These references receive messages of any type and context, and relay them to their associated actors, which may or may not respond to. This technique grants the actor a complete freedom to choose what to do and what to share, and is called message-passing. It’s the opposite to the more “traditional” way of communicating with objects, method invocation, where an entity outside of the object is able to access its fields and invoke its methods.

Let’s model an entity called Foo that contains a value foo, in both techniques. In an imperative, object-oriented world which relied on method invocation, we would most likely create a Foo class with a private field called foo, along with its public setter and getter.

public class Foo {

private int foo;

public int getFoo() {

return foo;

}

public int setFoo(int foo) {

this.foo = foo;

return this.foo;

}

}

...

Foo someFoo = new Foo();

someFoo.set(42);

...

int foo = someFoo.getFoo(); // returns 42

In an actor-based world which relied on message-passing, however, we would create a Foo actor (well, maybe not for a simple POJO, but you get the gist) which also would contain a field named foo, but wouldn’t expose it in any way. Instead, it would define its own protocol on how to access and modify that field, and let its reference take care of capturing incoming requests. It would then be able to process those requests in its own pace, and might even choose to refuse them altogether.

// this bears the same name as the actual Foo actor, and is used to keep common stuff about Foo

// it's called a companion object, and is commonly used in the Scala world

object Foo {

case class Get()

case class Set(foo: Int)

case class Result(foo: Int)

}

class Foo extends Actor {

// we can safely define this as a "var" because all messages will be handled sequentially

var foo: Int = 0

// the Actor superclass contains the mailbox and handles the lifecycle by calling this method repeatedly

// the type of this method is "Receive", which is an alias for PartialFunction[Any, Unit], i.e. (Any => Unit)

def receive = {

// act on the case that the message that was received was of type Foo.Get

// the ! is an alias for the send function, so this is equivalent to sender.send(Foo.Result(foo))

case Foo.Get => sender ! Foo.Result(foo)

// act on the case that the message that was received was of type Foo.Set

case Foo.Set(newFoo: Int) => {

foo = newFoo

// sender is an implicit ActorRef variable defined on the Actor class...

// ...which refers to the sender of the message currently being handled

sender ! Foo.Result(foo)

}

}

}

val foo = system.actorOf(Props(classOf[Foo])) // see the "Instantiating Actors" section

// the ? method is an alias to "ask", which returns a Future that will be resolved "if" the actor chooses to reply

// send a request to set the foo to 42, and when the actor responds, do something with it

val future = foo ? Foo.Set(42)

future onComplete {

... // do some stuff

}

// even the Foo.Get operation is asynchronous, so we need to wait for the future to resolve

(foo ? Foo.Get) onComplete {

... // do some other stuff

}

Combined with the fact that an actor may or may not reply to a message, the asynchronicity of communicating with an actor introduces another level of indirection, along with a fair amount of uncertainty, so even a simple getter/setter is difficult to implement with a traditional mindset (imperative and synchronous).

How do I know if my message is received? What if it was lost along the way? What if it did arrive at its destination, but the actor somehow ignored it, or its effects were overridden by some other message? These are perfectly valid questions, but actor systems are built around the “let it crash” philosophy. They acknowledge the fact that no communication medium is 100% efficient, and even if it were, various other kinds of failures are highly likely to occur, so they just let it happen, and find out ways to “heal” the damage of such failures. They replace failing actors, or even entire cluster nodes, and even under excruciatingly heavy load, they can spawn millions of actors or several new cluster nodes.

Since the actor model itself is inherently scalable and fault-tolerant, the real problem is modeling a data flow pattern that is resilient against losses, delays and errors. That’s a bit out of the scope of this article, so for now, let’s just say that we’ll touch on some of these patterns as we go along with coding examples in future articles.

Akka #

Akka is an open-source framework that implements the actor model for the JVM and .NET (see Akka.NET). It was created by Jonas Bonér back in 2009, and is currently being maintained by Lightbend (formerly Typesafe), also the current maintainer of Scala, Play! Framework and Apache Spark, and the driving force behind the Reactive Manifesto.

Like their conceptual counterparts, Akka’s actors, too, encapsulate both state and behaviour, communicate asynchronously, run an internal logic that only processes one message at a time, form hierarchies, and have unique addresses, but there are of course a handful of key concepts that are specific to Akka’s own implementation of actors. Let’s find out what they are.

Actor System #

In Akka, the universe in which the actors exist is called an actor system. It’s implemented by the aptly-named class ActorSystem, which not only serves as a factory to instantiate new actors (you can’t just call new Actor(...) to create an actor, but more on that later), but also as a gateway to look up actors (how else would you find a certain actor?). If configured properly, it can also act as a server to allow other processes or remote machines to create and/or look up, and communicate with actors on the system.

One thing to keep in mind about actor systems is that while it’s perfectly possible to have more than one actor systems per process, it’s advisable to use just one, as they’re a pretty heavy structure with multiple live threads [1] [2].

To create an actor system, simply call the create() or apply() (or one of their overloads) methods of the ActorSystem companion object.

// invoke the `apply(name: String)` method on the ActorSystem companion object

val system = ActorSystem("MySystem")

// invoke the `create()` method directly

// when no name is provided, the string "default" is used by default

val otherSystem = ActorSystem.create()

Actor Reference #

The base class for actors is the Actor class, but as per the model’s requirements, no Actor instance is accessed directly. Each actor has a reference that’s associated with it, and any communication with the actor is performed through this reference. It’s implemented by the ActorRef class, which contains a method called send that can be used to send the actor a message, and exposes nothing about the actor that it’s shadowing.

It’s worth noting that the ActorRef is a direct reference to an actor, and therefore will send any incomming messages to the actor system’s deadLetter channel (where messages that couldn’t arrive at their destinations are stored) when the actor it’s associated with it stops.

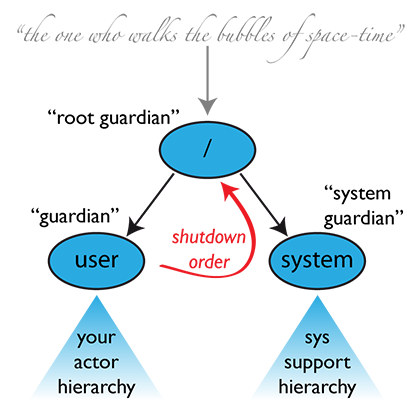

Actor Hierarchy and Guardian Actors #

When an actor system is created, it instantiates 3 top-level actors (also called the “guardians”): root, system and user. Being at the top-most level, the root guardian acts both as the entry point of the actor system, and also as the final stop in the case of a fatal all-systems failure (i.e. it’s the last actor that shuts down when a fatal error occurs, see the “shutdown order” on the image below). Not to be confused with the actor system itself, right below the root guardian, the system guardian acts both as the grand-parent of all system-related actors (i.e. loggers), and as the last stop before the root guardian in case of failure. At the same level of the system guardian is the user which serves both as the grand-parent of all user-created actors, and also as the last stop before the system guardian in case of failure.

With the exception of the root guardian, every Akka actor has a parent that’s determined at the time of the actor’s creation. For the top-most level actors this is the user guardian, and for others it’s the actor that requested its creation.

Actor Context #

Contextual information about an actor is grouped under an implicit immutable val called context of type ActorContext. This includes ActorRefs to the actor’s parent, its children, the sender of the message that’s being handled, and the actor itself, and also the properties with which the actor was created, and a reference to the system the actor is on. Aside from fields and properties, the context object also has a method to change the behavior of an actor (i.e. become and unbecome), and a bunch of others to instantiate actors (which would end up as its children) in various fashion.

The ActorSystem and ActorContext are both an implementation of the interface ActorRefFactory, so they resemble each other quite a bit.

Instantiating Actors #

There’s nothing in Akka that prevents you from instantiating an actor by simply calling new Actor(...), but then the actor wouldn’t be able to tell anything about its context (i.e. the actor system it was defined in, which actor was its parent, etc.), not to mention that the rule of actor encapsulation would be broken (you would have a direct reference to the actor instance!)

[3], so the proper way to create an actor is to let the actor system do it.

This can be done using the actorOf(props: Props): ActorRef (or its other variant that accepts a name for the actor, actorOf(props: Props, name: String): ActorRef) method found on the actor system. The same methods are also defined on the ActorContext class, and the difference between using those defined on the context rather than the system, is that, calling the context’s methods would set the actor that’s bound to the context as the parent of the newly-created actor, whereas the system would set it to the user guardian.

Props is a generic class that tells the actor system what type of actor to create, and which parameters to create it with. Consider the following example:

class Bar(baz: Int) extends Actor {

...

}

...

// create an actor of type Bar with its baz set to 42

val bar = system.actorOf(Props(classOf[Bar], 42))

Notice the extra use of classOf and brackets? As more and more actors are created throughout the codebase, those calls might make the code less and less readable. To prevent this, the general convention is to use a companion object containing a method to create the necessary Props object. Here’s the same Bar class, updated according to convention

[4]:

object Bar {

def props(baz: Int): Props = Props(classOf[Bar], baz)

}

class Bar(baz: Int) extends Actor {

...

}

...

val bar = system.actorOf(Bar.props(42))

In these examples, the Bar actor was created directly by the system, so it became a child of the user guardian. Actors such as these are called top-level actors, and it’s good practice to implement as little of them as possible

[5]. If we had another actor named Foo and we were to follow this principle, we would end up doing something like this:

object Foo {

def props(): Props = Props(classOf[Foo])

}

class Foo extends Actor {

...

}

object Bar {

def props(baz: Int): Props = Props(classOf[Bar], baz)

}

class Bar extends Actor {

def receive = {

case "begin" => context.actorOf(Foo.props) // create a child actor of type Foo

}

}

...

val bar = system.actorOf(Bar.props(42))

bar ! "begin" // an actor of type Foo will be created as the child of the actor "bar"

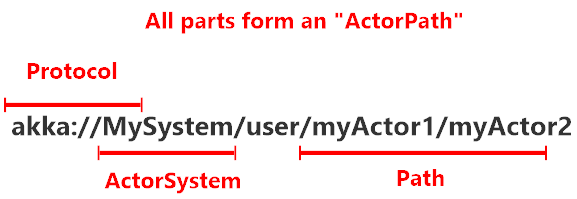

### Actor Path Each actor has a name, and it can either be specified at the time of the actor’s creation, or be left to the actor system to auto-generate. Considering that each actor also has a parent, there occurs a naturally-formed sequence of names that start from the actor system, and goes up to the actor itself as we follow the parent-child relationships of an actor. If we combine this we get a (hopefully) unique path which we can call the actor path and use to locate a certain actor.

Typically, an actor path consists of a protocol prefix, followed by the name of the actor system, and then the name of the actor system. Therefore, a SomeActor that operates under an actor system named SomeActorSystem would have the following path:

akka://SomeActorSystem/user/SomeActor

Likewise, if we were to have our SomeActor create another actor named SomeOtherActor, the path to that actor would become:

akka://SomeActorSystem/user/SomeActor/SomeOtherActor

As I’ve already stated before, actor systems can be configured to run as a server, and handle remote actor lookup requests. In such cases, actor paths naturally contain information about the remote aspects of the actor system, such as the transport mechanism, which is added to the protocol prefix, and the hostname and the port number which are added to the name of the actor system.

For instance, if our actor system was configured to work remotely through the TCP port 9001 on a machine with the IP address 123.45.67.89, we could access the actors I’ve previously mentioned through the following addresses:

akka.tcp://[email protected]:9001/user/SomeActor

akka.tcp://[email protected]:9001/user/SomeActor/SomeOtherActor

Looking Up Actors with Actor Selection #

The actor context does contain references to an actor’s parent and children, but that may not always be enough. What if you’d like to send a message to an actor’s siblings, its grandparent, or even a totally unrelated actor? Also, if I know that the actor I’m trying to locate is on the same actor system as I am, why do I have to keep entering the name and address of the actor system to find that actor?

Akka allows you to look up actors along its hierarchy via the class ActorSelection, either by an absolute or relative path, which may contain wildcards. This is particularly useful when you don’t know the exact path of an actor (remember that paths must be unique), or when you want to multicast messages to multiple actors.

Let’s look at a few examples:

// send a message to the sibling named "Foo"

context.actorSelection("../Foo") ! ...

// send a message to Bar's child, AntoherFoo

context.actorSelection("/user/Bar/AnotherFoo") ! ...

// send a message to Bar's children whose name starts with Baz

context.actorSelection("/user/Bar/Baz*") ! ...

// send a message to all third-level children with the name Buzz

context.actorSelection("/user/*/Buzz") ! ...

While ActorRef is a direct reference that points to one and only one actor (see Actor Reference section), and an actor selection is reusable and can point zero or more actors, you might still need that exact ActorRef that the ActorSelection matches. To do that, you simply send the actor selection an Identify message, and wait for an ActorIdentity(ref: ActorRef) message to arrive, after which you can use the sender or the return value of the Identity.getRef(): Optional[ActorRef] method to find out the ActorRef.

class Baz extends Actor {

// initially unknown

var bar: ActorRef = _

def receive = {

// use pattern matching to reduce Option[ActorRef] to ActorRef

case ActorIdentity(ref: ActorRef) => bar = ref

}

override def preStart() = {

context.actorSelection("/user/Foo/Bar") ! Identify

}

}

The Identify message can receive an optional parameter which gets passed over to the corresponding ActorIdentity reply, so when you have to identify multiple ActorRefs, you can pass some sort of unique identifier to the Identify message to discern between them.

class Baz extends Actor {

// initialize an empty map of type String -> ActorRef

var bars: Map[String, ActorRef] = Map()

def receive = {

// again, use pattern matching to reduce results, and add the new association to the map

case ActorIdentity(id: String, ref: ActorRef) => bars = bars + (id -> ref)

}

override def preStart() = {

context.actorSelection("/user/Foo/Bar") ! Identify("bar")

context.actorSelection("/user/Foo/AnotherBar") ! Identify("anotherBar")

// this will not find any actor so it won't be matched by the receive method

// since we've specifically asked for an ActorRef, not an Option[ActorRef]

context.actorSelection("/user/NoSuchActor") ! Identify("nobody")

}

}

Actor Behavior #

An actor’s behavior is determined by its receive(message: Any): Unit method. This is a partial function of type Actor.Receive, an alias for PartialFunction[Any, Unit], and is called every time a message is received.

The specific implementation of receive can be replaced with another method of the same type at runtime, through the use of become(behavior: Actor.Receive) and unbecome() methods defined on the actor context. This allows for stateful behaviors, and can be used to turn actors into very simple finite state machines (for implementing more complex state flows, see

Akka FSM). Here’s an example:

object Door {

case object Open

case object Close

}

class Door extends Actor {

var isOpen = false

def receiveOpen: Actor.Receive = {

case Door.Open => sender ! "The door is already open!"

case Door.Close => {

isOpen = false

sender ! "The door is now closed."

// the receive method will be replaced by the receiveClosed method starting from the next message

context.become(receiveClosed)

}

}

def receiveClosed: Actor.Receive = {

case Door.Close => sender ! "The door is already closed!"

case Door.Open => {

isOpen = true

sender ! "The door is now open."

// the receive method will be replaced by the receiveOpen method starting from the next message

context.become(receiveOpen)

}

}

def receive = receiveOpen

}

Actor Stash #

In certain situations where an actor becomes temporarily unable to handle certain messages, you might want to keep those incoming messages somewhere safe, only to retrieve them back and start processing again when the actor goes back to its normal state. This is done via the Stash trait, which allows you to store the incoming message with the stash() method, and retrieve them back with the unstashAll() method.

One possible use case for this is private chatting, where you’d stop attempting to send messages when the connection is lost, keep them in the memory, and then retry sending them once the connection is established back again.

class ChatActor extends Actor with Stash {

def connecting: Receive = {

case String => stash() // still not connected, stash the message

case ConnectionEstablished => {

// connection established, unstash all messages and go into the connected state

unstashAll()

context.become(connected)

}

}

def connected: Receive = {

case msg: String => target.send(msg) // send the message immediately

case ConnectionLost => {

// lost connection, go to "connecting" state and try reconnecting

reconnect()

context.become(connecting)

}

}

def receive = connecting

override def preStart = {

reconnect()

}

}

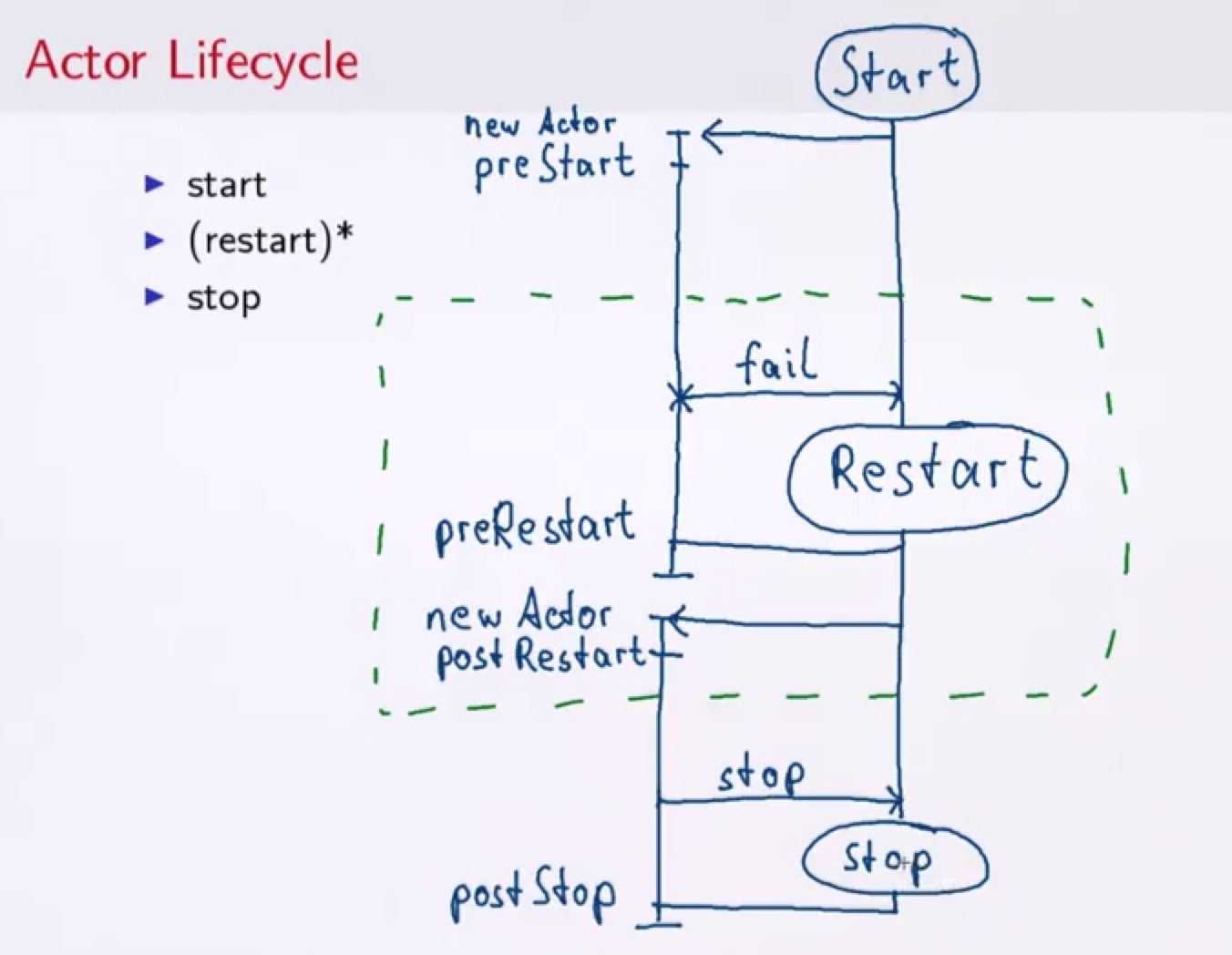

Actor Lifecycle #

While actors can be started and stopped, they also have the concept of restarts, where a failing actor can be replaced with another actor created with the same Props, to allow for more fault-tolerant and highly-available systems. As a developer, you might need to do some important stuff as these occur, like releasing resources when an actor’s stopped, or subscribing to a pub/sub channel before the actor starts.

These are done through the preStart(), postStop(), preRestart(reason: Throwable, message: Option[Any]) and postRestart(reason: Throwable) methods, which you can override to your liking. While all method names are self-explanatory, keep in mind that preRestart and postRestart methods are called on different actor instances; with the former being called on the failing actor, and the latter on the newly-created instance.

Here’s a snapshot from the Principles of Reactive Programming course:

Supervisor Strategies and Fault Tolerance #

What determines whether to restart the failing actor in case of a failure, or to bring down the entire system, is the fault tolerance levels of individual actors. Errors that are thrown from inside an actor’s receive loop is captured by its parent, and it’s that parent actor’s responsibility to decide what to do (in other words, the level of tolerance to apply). This is called supervisor strategy.

The list of possible actions an actor can take on a failure are as follows (note that these are all defined as objects on the akka.actor.SupervisorStrategy object, implementing the trait akka.actor.SupervisorStrategy.Directive):

Escalatethe failure that was caught by rethrowing it to the supervisor (so the responsibility is given to the parent of the parent actor that’s currently handling the error)Restartthe failing actor by destroying it and creating another actor with the samePropsin its place (see Actor Lifecycle)Resumethe message processing of the failing actor, effectively acting as if nothing happenedStopthe failing actor

Note: Restart, Resume and Stop also affects the children of the failing child actor, meaning that if it’s stopped, for example, its children are stopped too.

Each actor contains a supervisor strategy by default, and it’s determined by the implicitly-defined val supervisorStrategy of type SupervisorStrategy. It’s basically a Decider of type (Throwable => SupervisorStrategy.Directive) (i.e. PartialFunction[Throwable, SupervisorStrategy.Directive]), and by default it behaves as follows

[6]:

ActorInitializationException willStop` the failing child actorActorKilledException willStop` the failing child actorExceptionwillRestartthe failing child actor- Other types of

Throwablewill beEscalated to parent actor

This behaviour can be overridden as follows:

override val supervisorStrategy = {

case _ : NullPointerException => Resume // ignore NPEs

case _ : TimeoutException => Restart // restart on timeouts

case _ => Stop // stop for everything else

}

In the case of TimeoutException, our example behaves the same way as the default would, so if we wanted to be less verbose (which I usually don’t), we could’ve combined our own strategy with the default one:

override val supervisorStrategy = {

case _ : NullPointerException => Resume

case t : TimeoutException => super.supervisorStrategy.decider.apply(t) // leave it up to the default strategy

case _ => Stop

}

While we’ve only applied the Stop, Resume and Restart actions to the failing actor (and its descendants), we might have also wanted to apply them to the actor’s siblings as well. Furthermore, we might have wanted to keep count of the number of restarts we’ve performed (optionally in a certain time window), and stop the actor once a certain threshold was passed. and still lets us make our own decisions on what to do.

Akka implements two built-in strategies for these kinds of situations: OneForOneStrategy and AllForOneStrategy. As the names imply, the first one only affects the failing actor, and second affects both the failing actor and its siblings. Both of the strategies still allow you to make your own decisions on failures, so they can be considered as just another level of abstraction.

// let the default decision rules apply, but stop the actor if it gets restarted 5 times in one minute

override val supervisorStrategy = OneForOneStrategy(maxNrOfRetries = 5, withinTimeRange = 1 minute)

// allow up to 5 restarts per minute, and stop all children if that threshold is passed

// or an error other than TimeoutException is received

override val supervisorStrategy = AllForOneStrategy(maxNrOfRetries = 5, withinTimeRange = 1 minute) {

case _ : TimeoutException => Restart

case _ => Stop

}

Stopping an Actor #

There are several ways to stop an actor. One is through the stop(ref: ActorRef) method found on the actor context, which you may pass the ActorRef of the actor you want to stop, such as the actor’s own reference, self. This is an asynchronous operation and it stops the actor right after it finishes processing its current message (if any), so if there are any other messages queued up in the actor’s mailbox, they end up in the deadLetter queue of the actor system. The postStop() hook we’ve mentioned in the Actor Lifecycle section is triggered once the actor fully stops.

Another way to stop an actor is to send it a PoisonPill message. Like any other message, the PoisonPill ends up as the last item on the actor’s mailbox, so it allows the actor process any other messages that comes before it. As for the other messages, they end up in the deadLetter queue, just like in the case of context.stop().

There’s also the Kill message, which causes the actor to throw an ActorKilledException, so it’s up to the supervision strategy to determine its outcome; which, by default, is to Stop the actor, as we’ve already seen in the Supervisor Strategies and Fault Tolerance section.

Conclusion #

The actor model is a reasonably broad subject, so a single blog article filled mostly with theoretical stuff can barely scratch the surface. In the next article we’ll move on to more practical stuff like creating an empty Akka project from scratch, or making a simple hot-or-cold game based on that, so if you’re still interested in more reading material, just visit the links found in the Sources section.

Sources #

- Scala Documentation - Akka

- Java Champion Jonas Bonér Explains the Akka Platform - Oracle

- Erlang and its “99.9999999% uptime”

- Spotlight: ActorSelection, Watch and Identify - Let it Crash

- “What is it like to use Akka in production?” - Quora

- Case Studies and Stories - Lightbend

References #

- [1] Akka Documentation - Actor Systems

- [2] Viktor Klang (deputy CTO, Lightbend) - Comment on Stack Overflow

- [3] Akka Documentation - Actors - Dangerous Variants

- [4] Akka Documentation - Actors - Recommended Practices

- [5] Viktor Klang (deputy CTO, Lightbend) - Comment on Stack Overflow

- [6] Akka Documentation - Fault Tolerance

- [7] Joe Armstrong (Erlang creator) - What’s all this fuss about Erlang?