Functional programming has been on the rise for quite some time now, and rightly so. Many non-functional programming languages had long adopted at least some amount of functional programming principles, and while Java had been lagging behind, it’s finally jumped on the bandwagon with the latest version, Java 8.

Functional programming is closer to mathematics than other programming paradigms such as procedural or object-oriented programming, so as one gains more and more experience on one of them, it gets more difficult for them to grasp the functional programming concepts. Even though I had a C/C++ background using function pointers, and a lot of Javascript experience using callbacks and methods such as Array.map(), I had a hard time understanding LINQ in C#. In that sense, it’s perfectly understandable for me that most Java programmers, even seasoned ones, are shying away from lambdas and streams and prefer to stick to good old lists and for loops in their daily usage.

In the light of that observation, I decided to write this article to help programmers establish a ground on what these “strange” facilities are. I will be explaining what streams and lambda expressions are, and which functional operations are executed and what does it mean to be executed lazily. Hopefully, this article will be helpful to both newcoming Java 8 programmers, and C# programmers who are not familiar with the LINQ API.

For a downloadable version of the examples in this article, visit the corresponding Gists at:

Java: https://gist.github.com/ygunayer/c8941775a36cc2c60ad4

C#: https://gist.github.com/ygunayer/9e2a67b020a3613900e3

Concepts #

Lambda Expressions (aka Anonymous Functions) #

A lambda expression (or an anonymous function) is an unbound function that can be defined and used anywhere, be it method parameters or even return values. Programmers with a C/C++ background might feel a bit more familiar with this concept as they’re probably used to passing around function pointers, and it’s safe to assume that every Javascript developer has at some point used an anonymous function as a callback.

To handle a lambda expression, Java first maps it to a special type called a functional interface and then executes a specific method found on that interface. These interfaces are defined as follows:

| Functional Interface* | Input Types | Output Types | Primary Method | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier<T> | None | T | get() | Returns a value of type T |

| Consumer<T> | T | None | accept(T) | Consumes a value of type T |

| BiConsumer<T, U> | T, U | None | accept(T, U) | Consumes values of types T and U |

| Function<T, R> | T | R | apply(T) | Consumes a value of type T and returns a value of type R |

| BiFunction<T, U, R> | T, U | R | apply(T, U) | Consumes values of types T and U, and returns a value of type R |

| UnaryOperator<T> | T | T | apply(T) | Consumes a value of type T and returns a value of type T |

| BinaryOperator<T, T> | T | T | apply(T, T) | Consumes two values of type T and returns a value of type T |

| Predicate<T> | T | boolean | test(T) | Consumes a value of type T and returns a boolean |

| BiPredicate<T, U> | T, U | boolean | test(T, U) | Consumes values of types T and U, and returns a boolean |

*: Since primitive types cannot be specified as type parameters, these interfaces all have overrides for primitive types, such as IntConsumer.

As you might have noticed, Java’s built-in functional interfaces only accept up to 2 input parameters. For more, you can either use a technique called Currying, which basically means nesting functional interfaces in each other, or you can also create your own functional interfaces. Here’s an example:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface FooConsumer<T, U, S> {

void accept(T t, U u, S s);

}

C#, on the other hand, maps them to two types: Action<T> and Func<T, R>, both of which are delegates themselves and can receive up to 16 parameters. A delegate in C# is like a function pointer from C/C++ but it’s type-safe and contains a built-in iterator for callees. This iterator allows multiple functions to register themselves on delegates so that they’re invoked when the delegate itself is invoked. If you want to learn more about delegates, simply visit the

MSDN article about delegates.

| Delegate | Input Types | Output Types | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action<T1..T16> | T1..T16 | None | Consumes up to 16 values of type T1 to T16 |

| Func<T1..T16, R> | T1..T16 | R | Consumes up to 16 values of type T1 to T16 and returns a value of type R |

| Predicate<T> | T | bool | Consumes a value of type returns a boolean |

Code-wise, a lambda expression is defined inside another method or function’s scope, so it doesn’t have an access modifier. Since its types can be inferred, it doesn’t need to explicitly define its parameter and return types either. Furthermore, if the expression is a one-liner and contains a single expression (i.e. a sum or product), it doesn’t even have to have a return statement and curly braces.

The short-hand method to define a lambda expression in Java is as follows (notice how Java uses the same arrow notation used in lambda calculus):

Java

...

(a, b) -> { return a + b; }

(a, b) -> a + b;

...

C#

...

(a, b) => { return a + b; }

(a, b) => a + b;

...

And a few actual implementations:

Java

public void someMethod() {

FooConsumer<String, String, String> foo = (a, b, c) -> {

System.out.println(a + ", " + b + " and " + c);

};

// outputs "One, Two and Three"

foo.accept("One", "Two", "Three");

// outputs "Six, Nine and Ten"

foo.accept("Six", "Nine", "Ten");

}

public void someOtherMethod() {

BiFunction<Integer, Integer, String> foo = (a, b) -> {

return "The product of " + a + " and " + b + " is " + (a * b);

};

String foo1 = foo.apply(5, 10);

String foo2 = foo.apply(3, 5);

// outputs "The product of 5 and 10 is 50"

System.out.println(foo1);

// outputs "The product of 3 and -5 is -15"

System.out.println(foo2);

}

C#

public void SomeMethod()

{

Action<string, string, string> foo = (a, b, c) =>

{

Console.WriteLine(a + ", " + b + " and " + c);

};

// outputs "One, Two and Three"

foo("One", "Two", "Three");

// outputs "Six, Nine and Ten"

foo("Six", "Nine", "Ten");

}

public void SomeOtherMethod() {

Func<int, int, string> foo = (a, b) => {

return "The product of " + a + " and " + b + " is " + (a * b);

};

string foo1 = foo(5, 10);

string foo2 = foo(3, 5);

// outputs "The product of 5 and 10 is 50"

Console.WriteLine(foo1);

// outputs "The product of 3 and -5 is -15"

Console.WriteLine(foo2);

}

Now that we now how to express an anonymous function, it’s trivial to compose a method that takes an anonymous function as a parameter:

Java

public void someLambdaMethodExecutor(BiFunction<Integer, Integer, Integer> fn) {

System.out.println("Result of fn(1, 2) is " + fn.apply(1, 2));

}

public void someLambdaMethodCaller() {

BiFunction<Integer, Integer, Integer> add = (a, b) -> {

return a + b;

};

// this is also valid

BiFunction<Integer, Integer, Integer> multiply = (a, b) -> a * b;

// outputs "Result of fn(1, 2) is 3"

someLambdaMethodExecutor(add);

// outputs "Result of fn(1, 2) is 2"

someLambdaMethodExecutor(multiply);

}

C#

public void SomeLambdaMethodExecutor(Func<int, int, int> fn)

{

Console.WriteLine("Result of fn(1, 2) is " + fn(1, 2));

}

public void SomeLambdaMethodCaller()

{

Func<int, int, int> add = (a, b) => { return a + b; };

// this is also valid

Func<int, int, int> multiply = (a, b) => a * b;

// outputs "Result of fn(1, 2) is 3"

SomeLambdaMethodExecutor(add);

// outputs "Result of fn(1, 2) is 2"

SomeLambdaMethodExecutor(multiply);

}

And if you want to generate and return a lambda expression:

Java

public BiFunction<Integer, Integer, Integer> SomeLambdaGenerator(String which) {

if ("add".equals(which))

return (a, b) -> {

return a + b;

};

else

return (a, b) -> {

return a * b;

};

}

public void SomeLambdaGeneratorCaller() {

BiFunction<Integer, Integer, Integer> add = SomeLambdaGenerator("add");

BiFunction<Integer, Integer, Integer> multiply = SomeLambdaGenerator("multiply");

// outputs "1 + 2 = 3"

System.out.println("1 + 2 = " + add.apply(1, 2));

// outputs "1 * 2 = 2"

System.out.println("1 * 2 = " + multiply.apply(1, 2));

}

C#

public Func<int, int, int> SomeLambdaGenerator(string which)

{

if (which == "add")

return (a, b) => { return a + b; };

else

return (a, b) => { return a * b; };

}

public void SomeLambdaGeneratorCaller()

{

Func<int, int, int> add = SomeLambdaGenerator("add");

Func<int, int, int> multiply = SomeLambdaGenerator("multiply");

// outputs "1 + 2 = 3"

Console.WriteLine("1 + 2 = " + add(1, 2));

// outputs "1 * 2 = 2"

Console.WriteLine("1 * 2 = " + multiply(1, 2));

}

Streams #

A stream is a special kind of collection that only evaluates its values when they’re requested. In other words, it’s a lazy collection. This laziness allows them to be unrestricted by the time factor and thus able to be used on collection of infinite or at least unknown sizes, without worrying too much about concurrency (more of that in a later topic!). The C#’s term for a stream is enumerable. Here’s the definition:

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<T> |

| C# | IEnumerable<T> |

Streams can be explored in a much more detailed fashion, but for the sake of simplicity I’ll pass the subject to a future article.

Creating a Stream #

Since the functional operations are only defined on the stream class. As before, we won’t go into too much detail and will stick to turning generic collections into streams instead. To do that in Java, simply call the stream() method of a generic collection and you’ll get an appropriate Stream<T> instance. In the case of C#, all collections implement the IEnumerable interface, and since this is where functional operations are declared, there’s nothing you need to do before using them. If somehow you stumble upon a collection that doesn’t extend IEnumerable and therefore not contain any functional operations, try calling the AsEnumerable() extension method.

Java

...

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5));

Stream<Integer> numberStream = numbers.stream();

...

Materializing a Stream #

Since streams are conceptually lazy, you’ll need to materialize them into generic collections when you want to do some constant-time operations with them (i.e. count their items). In Java, you’ll need to use the Collectors class to achieve this, and in C#, you can simply call the appropriate extension methods defined on IEnumerable<T>. Here’s the method to materialize a stream into a list (there’s more, of course, but they vary too much from Java to C#, for more information visit

Oracle Docs page for Java 8 Collectors or

MSDN page for C#’s IEnumerable methods):

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | collect(Collectors::toList()) |

| C# | ToList() |

Optional #

In Java, every instance of Object and its sub-classes can be null, so you have to manually check for null values in your business. The downside of traditional null-checking is that it’s error-prone because it’s incredibly easy to forget to do. The Optional<T> class introduced in Java 8 aims to overcome that by wrapping objects and requiring you to be explicit about null-checking. C# does not have a direct equivalent, but the ? suffix which is the equivalent of using Nullable<T> can be used to some extent.

In a functional programming perspective, Optional is a Stream with a single element, so the functional operations listed in the Functional Operations section does apply to it as well. One extra method that Optional defines is the ifPresent(Consumer<T> fn) method which invokes the provided lambda expression when the contained value is present, which can be extremely useful.

To wrap an object in an Optional, simply call the Optional.ofNullable(T t) method. And to create an empty Optional, do Optional.ofNullable(null).

public void optionalExample() {

Optional<String> someString = Optional.ofNullable("I'm here!");

// the type can be inferred, so no need to specify it explicitly

Optional<String> someAbsentString = Optional.ofNullable(null);

// outputs "Some String: I'm Here!"

someString.ifPresent(str -> System.out.println("Some String: " + str));

// does nothing

someAbsentString.ifPresent(str -> System.out.println("Some Absent String: " + str));

// outputs "someAbsentString present? No"

System.out.println("someAbsentString present? " + (someAbsentString.isPresent() ? "Yes" : "No"));

// this throws an exception!

// someAbsentString.get();

}

Functional Operations #

These functional operations are used to transform a stream into another without changing its integrity. This is essentially what makes streams inherently concurrent and thread-safe. Also, since streams are lazily evaluated, it is possible to queue up multiple functional operations without any interference. The queued operations will only be executed when the stream is collected, therefore will not cause too much performance hit. In fact, this property is what made LINQ-to-SQL possible in the first place.

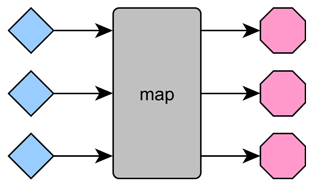

Map #

Based on a given transformation function, returns a new stream (not necessarily to different types or values) from a stream.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<R> map(Function<T, R> mapper) |

| C# | IEnumerable<R> Select(Func<T, R> mapper) |

| T: input, R: output |

Java

public void mapExample() {

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5));

List<Integer> mapped = numbers.stream().map(number -> number * 5).collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[5, 10, 15, 20, 25]"

System.out.println(mapped);

}

C#

public void MapExample()

{

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

var mapped = numbers.Select(number => number * 5).ToList();

// outputs "5, 10, 15, 20, 25"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", mapped));

}

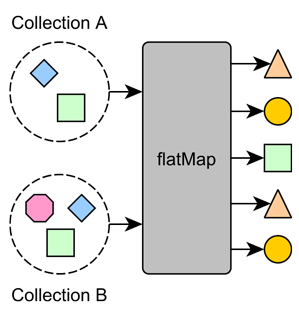

Flat Map #

Applies map to a stream and unfolds the returning stream. This is helpful in cases where your map function produces a collection but you want to group all output into a single collection.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<R> flatMap(Function<T, Stream<R>> mapper) |

| C# | IEnumerable<R> SelectMany(Func<T, IEnumerable<R>> mapper) |

| T: input, R: output |

Java

public void flatMapExample() {

Person john = new Person("John", Arrays.asList("John's Home", "John's Office"));

Person mary = new Person("Mary", Arrays.asList("Mary's Home"));

List<Person> people = new ArrayList<Person>(Arrays.asList(john, mary));

// notice how the return type is incorrect

List<List<String>> incorrect = people.stream().map(person -> person.getAddresses()).collect(Collectors.toList());

// notice how the return of Person::getAddresses() is turned back into a stream

List<String> allAddresses = people.stream().flatMap(person -> person.getAddresses().stream()).collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[[John's Home, John's Office], [Mary's Home]]" which is incorrect

System.out.println(incorrect);

// outputs "[John's Home, John's Office, Mary's Home]"

System.out.println(allAddresses);

}

C#

public void FlatMapExample()

{

var john = new Person()

{

Name = "John",

Addresses = new List<string>() { "John's Home", "John's Office" }

};

var mary = new Person()

{

Name = "Mary",

Addresses = new List<string>() { "Mary's Home" }

};

var people = new List<Person>() { john, mary };

// the type of this object is List<List<string>> which is obviously incorrect

var incorrect = people.Select(person => person.Addresses).ToList();

var allAddresses = people.SelectMany(person => person.Addresses).ToList();

// outputs two lists which is incorrect, we want a list of all addresses

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", incorrect));

// outputs "John's Home, John's Office, Mary's Home"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", allAddresses));

}

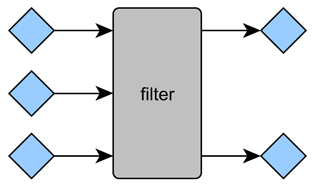

Filter #

Returns a new stream containing only the elements on a stream that passes the given predicate function.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<T> filter(Function<T, Boolean> predicate) |

| C# | IEnumerable<T> Where(Func<T, bool> predicate) |

Java

public void filterExample() {

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5));

List<Integer> odds = numbers.stream().filter(number -> number % 2 == 1).collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[1, 3, 5]"

System.out.println(odds);

}

C#

public void FilterExample()

{

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

var odds = numbers.Where(number => number % 2 == 1).ToList();

// outputs "1, 3, 5"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", odds));

}

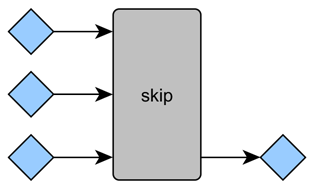

Skip #

Offsets a stream, returning a new stream containing the remainder of a stream after a given number of elements. Not technically a functional operation, but still useful with streams.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<T> skip(long count) |

| C# | IEnumerable<T> Skip(int count) |

Java

public void skipExample() {

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5));

List<Integer> remainder = numbers.stream().skip(3).collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[4, 5]"

System.out.println(remainder);

}

C#

public void SkipExample()

{

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

var remainder = numbers.Skip(3).ToList();

// outputs "4, 5"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", remainder));

}

Limit #

Limits a stream, returns a new stream containing the given number of elements taken from a stream.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<T> limit(long count) |

| C# | IEnumerable<T> Take(int count) |

Java

public void limitExample() {

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5));

List<Integer> taken = numbers.stream().limit(3).collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[1, 2, 3]"

System.out.println(taken);

}

C#

public void TakeExample()

{

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

var taken = numbers.Take(3).ToList();

// outputs "1, 2, 3"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", taken));

}

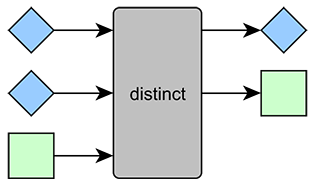

Distinct #

Returns a new stream containing only the unique elements in a stream. Used the the default equality comparer defined on the type T (equals in Java, Equals in C#).

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Java | Stream<T> distinct() |

| C# | IEnumerable<T> Distinct() |

Java

public void distinctExample() {

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 1, 2, 3, 5));

List<Integer> distinct = numbers.stream().distinct().collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[1, 2, 3, 5]"

System.out.println(distinct);

}

C#

public void DistinctExample()

{

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 1, 2, 3, 5 };

var distinct = numbers.Distinct().ToList();

// outputs "1, 2, 3, 5"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", distinct));

}

Sort #

Java and C# handle this differently. The sort method in Java, given a comparator function, sorts the elements in a stream into a new stream. In C#, however, the equivalent OrderBy method does not accept a comparative lambda expression, but rather, expects a lambda expression that returns a comparable data type. Since all types in C# have an implicit comparator function, it’s possible to simply provide which property to sort on, given a custom class.

Java

public void sortExample() {

Person john = new Person("John", Arrays.asList("John's Home", "John's Office"), 26);

Person mary = new Person("Mary", Arrays.asList("Mary's Home"), 25);

Person sean = new Person("Sean", Arrays.asList("Sean's Home"), 33);

List<Person> people = new ArrayList<Person>(Arrays.asList(john, mary, sean));

// this would fail since our Person class does not extend Comparable

// List<Person> sorted = people.stream().sorted().collect(Collectors.toList());

// this sorts people to their ages in a descending order

// it works because we're explicitly specifying how one person relates to another in terms of order

// also, if you wanted them in ascending order instead, simply reverse p1 and p2's ages in the subtraction

List<Person> sorted = people.stream().sorted((p1, p2) -> p2.getAge() - p1.getAge()).collect(Collectors.toList());

// outputs "[Sean (33), John (26), Mary (25)]"

System.out.println(sorted);

}

C#

public void SortExample()

{

var john = new Person()

{

Name = "John",

Addresses = new List<string>() { "John's Home", "John's Office" },

Age = 26

};

var mary = new Person()

{

Name = "Mary",

Addresses = new List<string>() { "Mary's Home" },

Age = 25

};

var sean = new Person()

{

Name = "Sean",

Addresses = new List<string>() { "Sean's Home" },

Age = 33

};

var people = new List<Person>() { john, mary, sean };

// sorts people to their ages in a descending order

var sorted = people.OrderByDescending(x => x.Age).ToList();

// outputs "Sean (33), John (26), Mary (25)"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", sorted));

}

Reduce #

Also known as aggregate. Given an initial value and a combinator function, iterates over a stream and produces a final, scalar result. For example, the sum of a stream is a reduce operation with an initial value of 0 and a combinator function that adds two values to each other. The idea behind collector methods such as Collectors.toList() is also this, they start with an initially empty collection and add to it while they iterate over the stream.

Java

public void reduceExample() {

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>(Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5));

int sum = numbers.stream().reduce(50, (a, b) -> a + b);

// we can emulate collect(Collectors.toList()) using the reduce operation!

// this overload of the method reduce() accepts three parameters: initial value, accumulator and combiner

// the accumulator function accumulates an item from the stream into the current accumulation

// and the combiner function is used to combine two accumulations in case they run in parallel

// so it's safe to say that the combiner function is a fail-safe mechanism for concurrency cases

List<Integer> asList = numbers.stream().reduce(new ArrayList<Integer>(), (list, number) -> {

list.add(number);

return list;

}, (list1, list2) -> {

list1.addAll(list2);

return list1;

});

// outputs "65"

System.out.println(sum);

// outputs "[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]"

System.out.println(asList);

}

C#

public void ReduceExample()

{

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

var sum = numbers.Aggregate(50, (a, b) => a + b);

// we can emulate IEnumerable.ToList() using the reduce operation!

var asList = numbers.Aggregate(new List<int>(), (list, number) =>

{

list.Add(number);

return list;

});

// outputs "65"

Console.WriteLine(sum);

// outputs "1, 2, 3, 4, 5"

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(", ", asList));

}

Conclusion #

Well, that’s it for this article. I hope it’s been helpful. There’s more to talk about functional programming, of course, and especially regarding how it’s inherently more suited for concurrent/parallel programming, but that topic’s for another article, hopefully.