In previous articles we’ve talked about how we can implement a simple game using actors, and how we can use Akka’s remoting functions to build actor networks, so it’s time we put the pieces together and create a multiplayer game.

The game we’ll implement is called pişti or bastra, a card game that can be played with 2 to 4 people, and is pretty popular among people of all ages due to its simplicity.

At the start, each player is dealt 4 cards, and 4 other cards are placed in the middle of the table (also called the board), with one of them open. To ensure fairness, any jacks that are dealt on the board stack is randomly replaced with another from the deck so the players can get them later. On each turn, a player plays a card from their hand and places it on the board. If the card that is played is a jack, or if it matches the one on top of the board stack, the player collects the board (also called fishing) and earns points. If not, the card is left on the stack and the turn passes over to the next player. If the player runs out of cards they’re dealt 4 more, and the game lasts until all cards are played out. Once they are, whoever has the highest score wins the game.

Rules #

There are different versions of bastra that have different scoring rules, but the one we’ll implement (possibly the most common one) goes like this:

- Jacks or aces are worth 1 point

- Two of clubs is worth 2 points

- Ten of diamonds is worth 3 points

- Performing a bastra (i.e. fishing a single card from the board using the same card) is worth 10 points

Planning #

Before moving on to the implementation, let’s plan our approach.

Dedicated Servers or Peer-to-Peer #

Whether or not a game should have dedicated servers to run the game logic on, or would P2P with a “master” peer suffice, is the age old problem for multiplayer games. The latter method is sometimes the go-to solution for even big companies since it basically induces no cost for server maintenance, but it’s susceptible to cheating and hacking, as was the case in many Call of Duty games. It’s not very difficult to alter the program’s memory and mess up with the game logic, and that’s how modern bots, wall hacks and aimbots work anyways.

Since we’re dealing with a game logic that depends heavily (solely?) on memory (i.e. the game state), there’s no way we can make our game cheat-proof if we run P2P. As such, we’ll create dedicated servers that keep the game’s state and run its logic, and verify clients’ commands as they come.

Communication Flow #

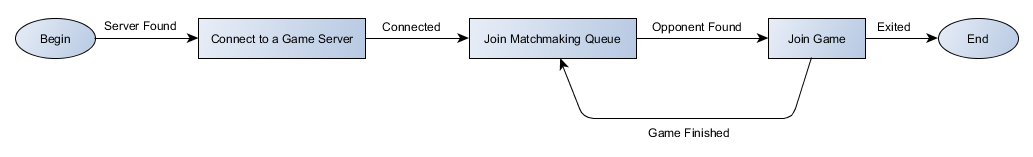

The flow of communication is the main topic of this article, so we’ll delve more deeply into this in following sections, but let’s see the outline first.

Since we’re not running a P2P network, it’s our servers’ responsibility to peer clients together and manage the flow of information. So the first thing we need to do is to let clients find a game server and introduce themselves to it.

Once a client connects, the server put them in a matchmaking queue, and if there are at least two players, they will be put into a game room where the game will actually played. Once the game ends, they’ll be back in the matchmaking queue.

To summarize, here’s an overview of the client flow:

Scores and Matchmaking #

This post is more about the client-server communication in a multiplayer game than other aspects of multiplayer gaming such as scoring and matchmaking, so we won’t cover these here. They are, however, among the main topic of future posts, so please stay tuned. Until then, we won’t score players and the matchmaking will simply take the first two player in the queue and put them in a game.

That said, players do have to wait until they’re placed in a game, so we’ll call this state “waiting in the lobby”, and implement a special actor to handle it.

User Interaction and UI #

We need no user interaction on the server side (aside from logging stuff), and on the client side we’ll just go ahead and use the terminal for both input and output since we don’t have much visual data. Therefore, no UI.

Project Outline #

We’ll have one project each for both the server and the client, and another project called commons to that we can share the same domain objects and messages. Since we don’t need a professional-grade project structure, we’ll simply create a multi-project setup.

Here’s what the folder structure looks like at first:

(workspace folder)

|

\- bastra

+- .gitignore

+- build.sbt

+- client

| +- src

| | \- main

| | \- scala

| | \- com

| | \- yalingunayer

| | \- bastra

| | \- BastraClient.scala

| \- build.sbt

+- commons

\- server

+- src

| \- main

| \- scala

| \- com

| \- yalingunayer

| \- bastra

| \- BastraServer.scala

\- build.sbt

Implementation #

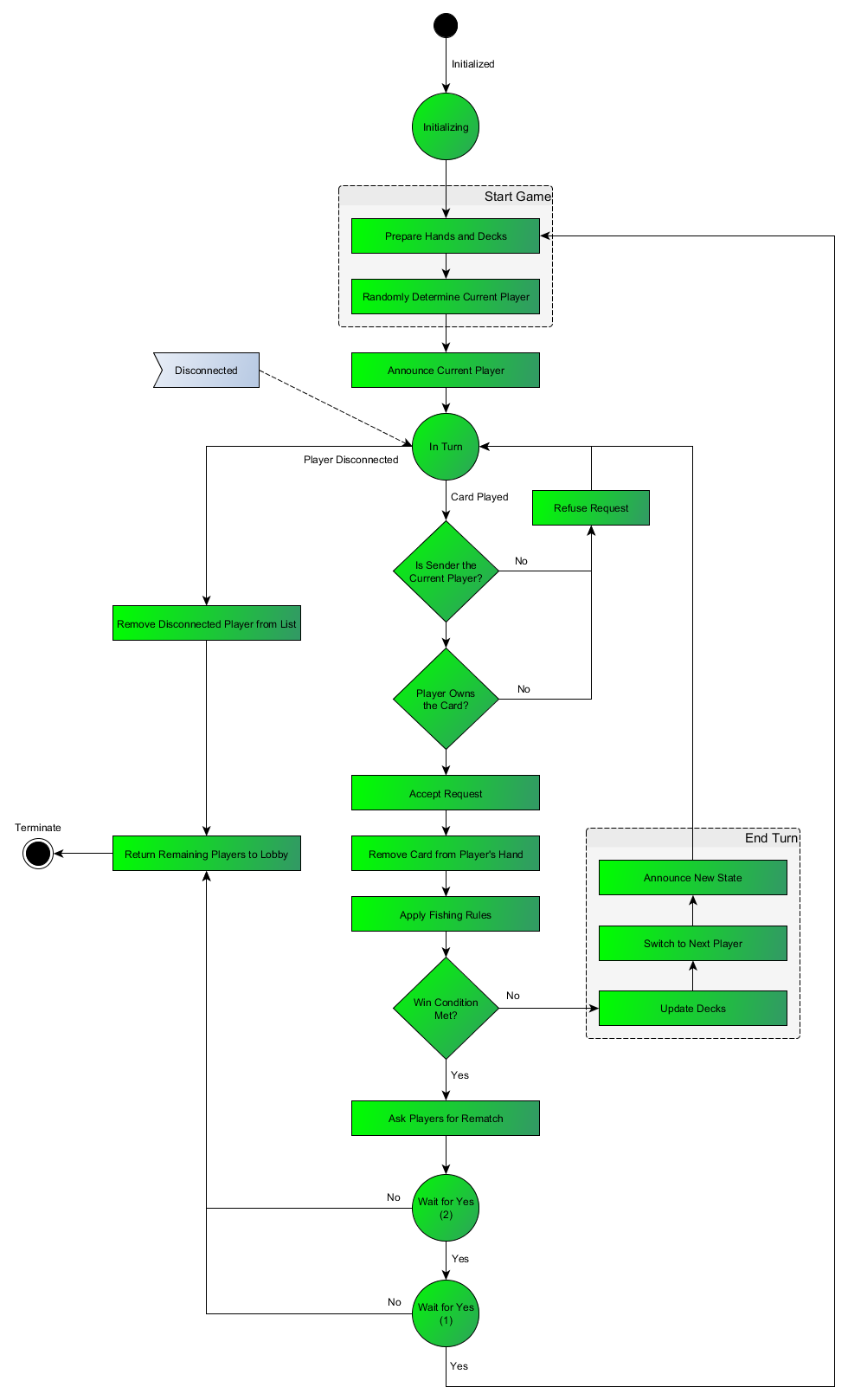

The codebase for this project is considerably larger than previous examples, so rather than going line by line over the code, I’ll try to explain it by going over flowcharts and samples of code. The codebase has a sufficient (hopefully) amount of comments as well, so we should be fine.

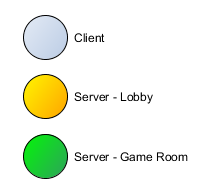

P.S. Since we have multiple actors running different state machines, I’ve colored their diagrams differently. Use the following legend if needed.

Domain Objects #

Since we’re making a card game our domain objects are cards, decks, ranks and suits, and we can implement a few case classes and companion objects to represent them with convenience.

Suits #

Suits basically represent the class or category of a card, and consists of a name and a symbol. The following is a list of suit names and their symbols.

| Suit Name | Symbol |

|---|---|

| Clubs | ♣ |

| Spades | ♠ |

| Diamonds | ♦ |

| Hearts | ♥ |

We can represent these as follows:

abstract class Suit(val name: String, val shortName: String) extends Serializable

...

object Suit {

case class Clubs() extends Suit("Clubs", "♣")

case class Spades() extends Suit("Spades", "♠")

case class Diamonds() extends Suit("Diamonds", "♦")

case class Hearts() extends Suit("Hearts", "♥")

def all: List[Suit] = List(Clubs(), Spades(), Diamonds(), Hearts())

implicit def string2suit(s: String) = s match {

case "♣" => Clubs()

case "♠" => Spades()

case "♦" => Diamonds()

case "♥" => Hearts()

case _ => throw new RuntimeException(f"Unknown suit ${s}")

}

}

Ranks #

Ranks represent the value of a card, and have a special ordering such as A, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, J, Q, K, where A is sometimes larger than K and sometimes isn’t. Even so, we can just go ahead and implement this as follows:

abstract class Rank(val value: Int, val name: String, val shortName: String) extends Serializable

...

object Rank {

case class Ace() extends Rank(14, "Ace", "A")

case class Two() extends Rank(2, "Two", "2")

case class Three() extends Rank(3, "Three", "3")

case class Four() extends Rank(4, "Four", "4")

case class One() extends Rank(5, "Five", "5")

case class Six() extends Rank(6, "Six", "6")

case class Seven() extends Rank(7, "Seven", "7")

case class Eight() extends Rank(8, "Eight", "8")

case class Nine() extends Rank(9, "Nine", "9")

case class Ten() extends Rank(10, "Ten", "10")

case class Jack() extends Rank(11, "Jack", "J")

case class Queen() extends Rank(12, "Queen", "Q")

case class King() extends Rank(13, "King", "K")

def all: List[Rank] = List(Ace(), Two(), Three(), Four(), One(), Six(), Seven(), Eight(), Nine(), Ten(), Jack(), Queen(), King())

implicit def string2rank(s: String) = s match {

case "A" => Ace()

case "2" => Two()

case "3" => Three()

case "4" => Four()

case "5" => One()

case "6" => Six()

case "7" => Seven()

case "8" => Eight()

case "9" => Nine()

case "0" => Ten()

case "J" => Jack()

case "Q" => Queen()

case "K" => King()

case _ => throw new RuntimeException(f"Unknown rank ${s}")

}

Cards #

We usually have two ways to refer to a card: “Ace of Spades” or “A♠”. We can call these the name and short names, and with suits and ranks implemented, it’s easy to create a class that can represent both.

case class Card(val rank: Rank, val suit: Suit) {

def name(): String = f"${rank.name} of ${suit.name}"

def shortName(): String = f"${rank.shortName}${suit.shortName}"

def score(): Int = {

(rank, suit) match {

case (Rank.Two(), Suit.Clubs()) => 2

case (Rank.Ten(), Suit.Diamonds()) => 3

case (Rank.Jack(), _) => 1

case (Rank.Ace(), _) => 1

case _ => 0

}

}

def canFish(other: Card) = {

if (rank == Rank.Jack()) true

else this == other

}

override def toString(): String = shortName

}

Decks #

A regular deck consists of 52 cards, one from each suit and rank. Let’s put this on the Card class.

object Card {

private val pattern = "^([AJKQ2-9])\\s*([♣♠♦♥])$".r

def fullDeck: List[Card] = for {

suit <- Suit.all

rank <- Rank.all

} yield Card(rank, suit)

implicit def string2card(s: String): Card = s match {

case pattern(rank, suit) => Card(rank, suit)

case _ => throw new RuntimeException(f"Invalid card string ${s}")

}

}

A list of cards isn’t exactly a domain object, we can’t really build on that, so let’s abstract that into another class called CardStack. This will allow us to generate ordered or randomly ordered decks, and with or without a specific card.

object CardStack {

def sorted: CardStack = CardStack(Card.fullDeck)

def shuffled: CardStack = CardStack(scala.util.Random.shuffle(Card.fullDeck))

def empty: CardStack = CardStack(List())

implicit def cards2stack(cards: List[Card]): CardStack = CardStack(cards)

}

case class CardStack(val cards: List[Card]) {

def removed(card: Card): CardStack = CardStack(Utils.removeLast(cards, card))

override def toString(): String = cards.mkString(", ")

}

Establishing the Connection #

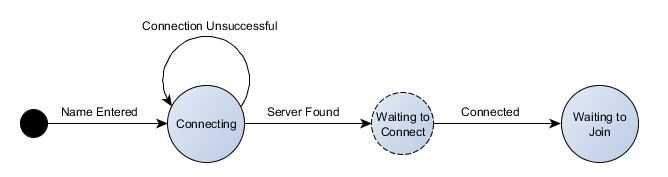

Now that we’ve created our domain objects, it’s time to implement the flow. Looking back at the overview in the previous section, our first task is to connect the client to a server. In order to do that, we’ll simply let the client connect to a specific actor system on a specific IP address and port. In the ideal world this is pretty much the same, only the IP address is replaced by a hostname, quite possibly prefixed by a region code. Here’s an example: eu.logon.worldofwarcraft.com

One thing to note here is that there are dozens of reasons that we can’t establish the connection in the first attempt (if the client doesn’t have an internet connection we may never connect at all!), so we’ll let the client retry connecting every 5 seconds.

Also, we need a name for each player since we want to introduce them to their opponents, so we ask the player their name before initiating the connection request. This also acts as a pseudo-login phase which we might need in future examples.

Here’s the client’s state diagram for the connection phase:

And here’s an excerpt from the client code that implements this flow.

class PlayerActor extends Actor {

...

def tryReconnect = {

def doTry(attempts: Int): Unit = {

context.system.actorSelection("akka.tcp://[email protected]:47000/user/lobby").resolveOne()(10.seconds).onComplete(x => x match {

case Success(ref: ActorRef) => {

println("Server found, attempting to connect...")

server = ref

server ! Messages.Server.Connect(me)

}

case Failure(t) => {

System.err.println(f"No game server found, retrying (${attempts + 1})...")

Thread.sleep(5000) // this is almost always a bad idea, but let's keep it for simplicity's sake

doTry(attempts + 1)

}

})

}

println("Attempting to find a game server...")

context.become(connecting)

doTry(0)

}

override def preStart(): Unit = {

println("Welcome to Bastra! Please enter your name.")

Utils.readResponse.onComplete {

case Success(name: String) => {

me = Player(Utils.uuid(), name)

tryReconnect

}

case _ => self ! PoisonPill

}

}

...

}

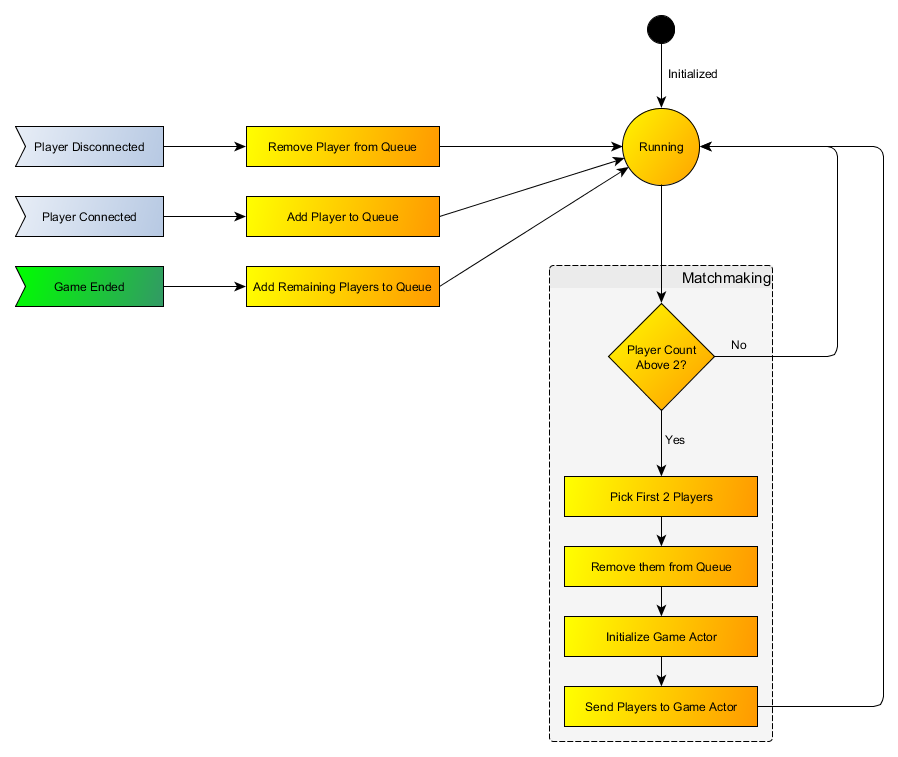

Matchmaking #

The matchmaking is performed on the server’s end, and as stated in the previous section it’s really nothing special. For the sake of completeness, I’ve also included the initialization phase.

Game Logic #

We’ve finally found a match, so it’s time to run the game logic now!

As always, our game room actor will be responsible for not only running the game logic, but also watching the players’ connections and terminating if one of them disconnects. Upon termination, it should also return whoever’s left in the room to the lobby so they can play another game.

As for the client, remember that in previous sections we left them in the lobby, and now it’s time to let them into a game. They’ll start out from the matchmaking phase and will then begin waiting for the game to start. As seen on the server’s flow, it’ll first prepare the deck and decide on who’s going first, announce these details and then give the turn to a random player. We’ll have anticipate each step on our client.

With the flows in place, let’s implement the actual game logic. We’ll do this by keeping the game’s current state and updating it based on the cards played by the players, assuming that a valid card was played, and we’ll also keep the game score so we can determine the winner in the end. Looking at the game rules in the first section, here’s our ruleset:

- Only the player in turn can play a card

- A player can only play a card that they have in their hand

- When a card played, it’s removed from the player’s hand

- When a card is played on an empty board it’s placed on the board

- When a card is played on top of a card that it cannot match, it’s placed on top of the board stack

- When a card is played on top of a card that it can match, it’s placed on the player’s bucket along with all the cards on the board, and the player earns points. This is called fishing.

- If both players’ hands are empty upon removing a card, the game deals 4 cards to each player

- If the deck and both players’ hands are empty upon removing a card, the game ends, and the player who has the higher score is elected winner

Here’s one way of implementing these rules.

...

/**

* Determine the next state based on a card that was played

*/

def determineNextState(card: Card, playerInfo: PlayerInformation, opponentInfo: PlayerInformation, deckCards: List[Card], middleCards: List[Card]): StateResult = {

val player = playerInfo.state

val opponent = opponentInfo.state

// determine if the player has fished a card, what their scores will be, and what their bucket will contain on the next turn

// since this will also affect the middle stack, determine its new state as well

val (isFished, newScore, newMiddleStack, newBucketStack) = middleCards.headOption match {

case Some(other) if card.canFish(other) => {

val newBucketCards = card :: middleCards ++ player.bucket.cards

// find out if a bastra is performed

val isBastra = middleCards match {

case x :: Nil if (x == card) => true

case _ => false

}

val earnedPoints = (card :: middleCards).map(_.score).sum + (if (isBastra) 10 else 0)

val newScore = PlayerScore(earnedPoints + player.score.totalPoints, player.score.bastras + (if (isBastra) 1 else 0), newBucketCards.length)

(true, newScore, CardStack.empty, CardStack(newBucketCards))

}

case _ => (false, player.score, CardStack(card :: middleCards), player.bucket)

}

val proposedNextHand = player.hand.removed(card).cards

val bothHandsEmpty = proposedNextHand.isEmpty && opponent.hand.isEmpty

val isFinished = bothHandsEmpty && deckCards.isEmpty

val shouldDeal = !isFinished && bothHandsEmpty

// determine if we need to deal new cards to players

val (nextDeck, nextPlayerHand, nextOpponentHand) = shouldDeal match {

case true => (deckCards.drop(8), deckCards.take(4), deckCards.drop(4).take(4))

case _ => (deckCards, proposedNextHand, opponent.hand.cards)

}

val nextPlayerState = PlayerState(CardStack(nextPlayerHand), newBucketStack, newScore)

val nextPlayerInfo = PlayerInformation(playerInfo.session, nextPlayerState)

val nextOpponentState = PlayerState(CardStack(nextOpponentHand), opponent.bucket, opponent.score)

val nextOpponentInfo = PlayerInformation(opponentInfo.session, nextOpponentState)

val nextState = GameState(isFinished, CardStack(nextDeck), newMiddleStack, nextOpponentInfo, nextPlayerInfo)

// determine the winner (if any)

val winner: Option[PlayerInformation] = isFinished match {

case true => (nextPlayerInfo :: nextOpponentInfo :: Nil).sortBy(_.state.score.totalPoints).tail.headOption

case _ => None

}

StateResult(nextState, winner, isFished)

}

...

Ouch! This looks a bit messy and difficult to maintain, so we’d better write a few (albeit incomprehensive) unit tests for it. We’ll have three test cases; one for fishing a card, another for a regular round without fishing a card, and another to verify that the game successfully terminates when all cards are played out. So here they are, in order:

class GameRoomActorSpec extends FlatSpec with Matchers {

it should "fish when necessary" in {

val baseDeck = CardStack.sorted

val p1 = Player("foo", "Foo")

val p2 = Player("bar", "Bar")

val card: Card = "J♠"

val hand1: List[Card] = List("A♠", "2♠", "3♠", card)

val hand2: List[Card] = List("A♦", "2♦", "3♦", "4♦")

val middleStack: List[Card] = List("A♣")

val deck = baseDeck.removed(hand1 ++ hand2 ++ middleStack)

val player1 = PlayerInformation(PlayerSession(p1, null), PlayerState(hand1, CardStack.empty, PlayerScore.zero))

val player2 = PlayerInformation(PlayerSession(p2, null), PlayerState(hand2, CardStack.empty, PlayerScore.zero))

val result = GameRoomActor.determineNextState(card, player1, player2, deck.cards, middleStack)

result.winner should be (None)

result.newState.deck should be (deck)

result.newState.playerInTurn.state.hand should be (CardStack(hand2))

result.newState.playerWaiting.state.hand should be (CardStack(hand1).removed(card))

result.newState.playerWaiting.state.bucket should be (CardStack(card :: middleStack))

result.newState.middleStack.isEmpty should be (true)

result.isFished should be (true)

}

it should "not fish when not possible" in {

val baseDeck = CardStack.sorted

val p1 = Player("foo", "Foo")

val p2 = Player("bar", "Bar")

val card: Card = "4♠"

val hand1: List[Card] = List("A♠", "2♠", "3♠", card)

val hand2: List[Card] = List("A♦", "2♦", "3♦", "4♦")

val middleStack: List[Card] = List("A♣")

val deck = baseDeck.removed(hand1 ++ hand2 ++ middleStack)

val player1 = PlayerInformation(PlayerSession(p1, null), PlayerState(hand1, CardStack.empty, PlayerScore.zero))

val player2 = PlayerInformation(PlayerSession(p2, null), PlayerState(hand2, CardStack.empty, PlayerScore.zero))

val result = GameRoomActor.determineNextState(card, player1, player2, deck.cards, middleStack)

result.winner should be (None)

result.newState.deck should be (deck)

result.newState.playerInTurn.state.hand should be (CardStack(hand2))

result.newState.playerWaiting.state.hand should be (CardStack(hand1).removed(card))

result.newState.playerWaiting.state.bucket should be (CardStack.empty)

result.newState.middleStack should be (CardStack(card :: middleStack))

result.isFished should be (false)

}

it should "should end the round and elect a winner when no cards remain" in {

val baseDeck = CardStack.sorted

val p1 = Player("foo", "Foo")

val p2 = Player("bar", "Bar")

val hand1 = baseDeck.cards.take(4)

val hand2 = baseDeck.cards.drop(4).take(4)

val middleStack = baseDeck.cards.drop(8).take(4)

val deck = baseDeck.cards.drop(12)

val player1 = PlayerInformation(PlayerSession(p1, null), PlayerState(hand1, CardStack.empty, PlayerScore.zero))

val player2 = PlayerInformation(PlayerSession(p2, null), PlayerState(hand2, CardStack.empty, PlayerScore.zero))

// simulate the game by running playing the first card on all turns for each player

def playAllRounds(player: PlayerInformation, opponent: PlayerInformation, remaining: CardStack, middle: CardStack): GameRoomActor.StateResult = {

def doPlayRound(round: Int, player: PlayerInformation, opponent: PlayerInformation, remaining: CardStack, middle: CardStack): GameRoomActor.StateResult = {

if (round >= 1000) {

throw new RuntimeException("The game wasn't finished after 1000 rounds");

}

val card = player.state.hand.cards.head

val result = GameRoomActor.determineNextState(card, player, opponent, remaining.cards, middle.cards)

if (result.winner.isDefined) result

else {

val nextState = result.newState

doPlayRound(round + 1, nextState.playerInTurn, nextState.playerWaiting, result.newState.deck, result.newState.middleStack)

}

}

doPlayRound(0, player, opponent, remaining, middle)

}

val result = playAllRounds(player1, player2, deck, middleStack)

result.winner.isDefined should be (true)

}

}

Let’s find out if our tests actually pass:

$ sbt "project server" test

...

[info] GameRoomActorSpec:

[info] - should fish when necessary

[info] - should not fish when not possible

[info] - should should end the round and elect a winner when no cards remain

[info] Run completed in 337 milliseconds.

[info] Total number of tests run: 3

[info] Suites: completed 1, aborted 0

[info] Tests: succeeded 3, failed 0, canceled 0, ignored 0, pending 0

[info] All tests passed.

...

Building and Running #

The implementation phase is finally over, so it’s time to build the game and play it. To do that, we’ll use the same method as before (see the

previous article), but this time, since we’re using a multi-project setup, we’ll need to specify the project we’re building when running our stage command.

Server

$ sbt "project server" stage

Client

$ sbt "project client" stage

And, voila! We now have two executables for each app, and therefore can play the game! Let’s run the server first:

$ ./bastra-server/target/universal/stage/bin/bastra-server

Server is now ready to accept connections

...

And then the clients:

$ ./bastra-client/target/universal/stage/bin/bastra-client

Welcome to Bastra! Please enter your name.

> foo

...

$ ./bastra-client/target/universal/stage/bin/bastra-client

Welcome to Bastra! Please enter your name.

> bar

...

Here’s what the gameplay looks like:

Conclusion #

So that’s pretty much it for the “basic” implementation of a turn based multiplayer game. While we do have a fully functional gameplay, the game can only be served and played on the same machine, and it simply lacks a UI, but at least we’ve made some progress.

In upcoming articles we’ll take care of these issues. We’ll deploy the server on a separate machine, implement a simple UI so the game can be played on the browser, and also a WebSocket-based web application to acts as a gateway between the front-end and the game server. So stay tuned!

See the code at Github: https://github.com/ygunayer/bastra