I’ve recently had the opportunity to work with ANTLR to create a DSL, and I’ve liked the overall experience so much that I’ve started using it for parsing just about anything, especially for my metaprogramming needs, and decided to write a series of articles to explain how it can be used to create DSLs.

In the first article we’ll discuss the motivations behind creating a DSL, what our options are regarding the implementation, and how ANTLR can be used to declare a grammar and parse some inputs with it.

In later articles we’ll create an actual DSL, execute and evaluate inputs, and even write a web-based code editor with full support for parsing and verifying code written in our language.

For this we’ll be using Microsoft’s Monaco Editor so it’ll also double as a potential VS Code extension because VS Code is based on Monaco as well.

But first things first, let’s see why we might need a DSL in the first place.

An example DSL implementation using Antlr4 and Java

Motivation - Why Create a DSL? #

When building a product or a new feature for an already existing product, we sometimes “know” our user base well enough to have a firm grasp on what they would need, and sometimes we involve them personally in the process to learn what they actually need. When it’s time to iterate, we do feedback sessions to find out what their pain points are and what they would like to be added, and before launch we do A/B tests to see which out of a several options they would prefer.

All of these can be categorized as efforts produce the most generic and cross-cutting solution possible, and they surprisingly work. Though the needs are many and endless, the users compromise some of them to ultimately accept a solution that works well enough for the majority.

But sometimes the needs are so individually specific that there simply is no common ground. Where a solution might work perfectly for some, but might be unacceptable for the rest. Parameterized rule engines like fraud detectors, loyalty programs, chat bots and campaign selection engines are perfect examples for that, because not all parameter values can be globally acceptable.

And sometimes it’s not just about dealbreaker, but also the desire to have a product that is extensible, and offers a functionality that can cover as much ground as possible. The games industry has long adopted this approach with modding, and some games owe most of their success and shelf life to their modding capabilities, and some, like Half-Life, their very existence.

But how can we provide such endless possibilities to our users? Can we afford the cost of developing and maintaining convoluted user interfaces with full support of our feature? Do we have the backend to support that UI to begin with? Assuming we did both, will we even be able to explain those UIs to our users?

Let’s try to think outside of the box. What’s one thing that we can use to universally define and execute every single feature that we can think of? You guessed it, code. After all, that’s what we would be writing in order to implement that feature to begin with, right?

So do we allow our users to write their own code? Do we expect them to be programmers? Do we actually want to execute an arbitrary code to begin with? Certainly not!

So how about we create a custom scripting/programming language instead? This way not only we would get to have a language that is completely specific to our business (and as easy as to learn and use as possible), but we would also not have to worry about arbitrary code execution and the security compromises that come with it, because we would be able to fully control which data and functions would be available to the language. No need to sandbox code, or to review user submitted code for security purposes.

If you like the idea, I can welcome you to the world of domain-specific languages (DSLs).

Creating a DSL #

Creating a DSL entails coming up with a solution to parse some arbitrary input into a set of instructions that our program can understand, and executing those instructions with another set of inputs when required.

Some programming languages like Scala, Kotlin and Groovy have a syntax so concise and flexible that it’s possible to create DSLs using regular expressions and function calls. But these require prior knowledge of the language with somewhat of an advanced level, and also run the risk of locking you in to the language.

For a more universally passable solution we would need a specialized parser, and for that the solutions are just as many.

Regular expressions are a nice way to get started, and they do work well for small and simple DSLs, but they tend to get extremely tedious to work with especially when things get a little bit complicated. In particular, I’ve had the most trouble with;

- Processing multiline input

- Ignoring certain elements (e.g. whitespaces)

- Processing an arbitrary number of interspersed patterns

- Identifying and naming sub pattern captures in a consistent and concise way

- Choosing between a group or subgroup of subpatterns and identifying them

- Reusing parts of a pattern

And the list goes on, but that is to be expected. After all we’re creating a custom language, so we need and actual compiler, and this is not what regexes are for.

Writing a Compiler #

As soon-to-be language creators, we need to approach this with the degree of seriousness that it needs, and remember what computer science has taught us to do.

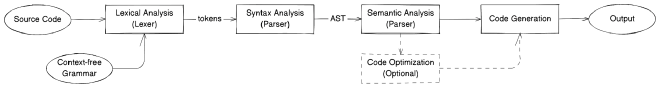

Looking at the diagram we find out that, in order to create a compiler for our language we need to:

- Come up with a context-free grammar for the language

- Run a lexer with that grammar for a given source code to produce a set of tokens

- Feed those tokens into a parser to generate an abstract syntax tree (AST)

- Have our semantic analyzer examine the AST to make sure it’s semantically valid

- Optionally feed the AST through an optimizer to crop out unnecessary code

- Finally produce an executable code from that AST and return it as the output

Assuming that we’ve created our grammar, and that we won’t need any optimization, all we need is a lexer to tokenize the input, and a parser to turn those tokens into an AST in our favorite programming language so we can validate and execute the AST.

Fortunately, there are many lexers and parser generators out there (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_parser_generators#Deterministic_context-free_languages), and some parser generators even have built-in lexers, reducing the number of steps required to process.

One such parser generator, and my go-to generic parser for quite some time, is ANTLR.

ANTLR #

ANTLR has a EBNF-like syntax for declaring grammars, and can produce lexers and parsers to parse a given code, and listeners and visitors to interface with the generated ASTs.

It can also inject arbitrary code into either the lexer or parser components, allowing further customizations and supporting more complex use cases such as counting bracket/parentheses for handling nested blocks, and also creating indent-sensitive languages like Python and Godot Engine’s GDScript.

As a JVM-based tool it can generate Java code, meaning that the output can be used in just about all JVM languages from Scala to Clojure, and it has built-in support for generating lexers and parsers in C++, C#, Go, JavaScript, Python, and PHP. Furthermore, there are projects like antlr_rust to extend the runtime language support even further.

What fascinates me most about ANTLR is that, because it can target a JavaScript runtime, we can use the same grammar on our frontend to parse an incoming source code, turn it into a set of tokens, validate the code both syntactically and semantically, and integrate everything with a solution like Microsoft’s Monaco Editor to create a built-in code editor on our web pages, with full support syntax highlighting and code validation for our custom language.

In fact, in the upcoming articles this is exactly what I’m going to do, so stay tuned!

Tooling #

ANTLR has been in development for quite a while now, and its creator, Terence Parr, is still very active in the ANTLR ecosystem. He’s personally built many tools to support the process of using ANTLR, but there are also many tools made by the community which is as active and mature as Parr himself.

Check out Parr’s video titled ANTLR v4 with Terence Parr where he talks about ANTLR in general.

Some of these amazing tools are listed at https://www.antlr.org/tools.html on the official project website, but I wanted to share some of the ones that I actively use.

IntelliJ Plugin #

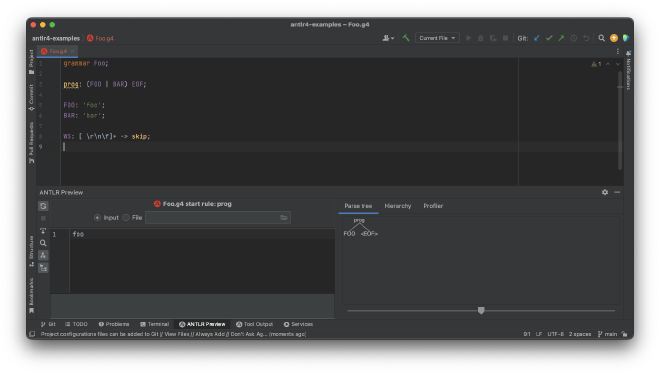

IntelliJ IDEA has an excellent ANTLR plugin that can not only syntax highlight and verify ANTLR grammars, but also produce visual ASTs and complexity reports. It also works for the community edition of IDEA so I highly recommend using it.

I find this plugin especially because as soon as you open an ANTLR grammar file the ANTLR Preview panel gets activated, which has a source input pane on the left, and a list of tabs on the right for examining the token hierarchy, which get updated automatically as you change the grammar or the source input.

VS Code Extension #

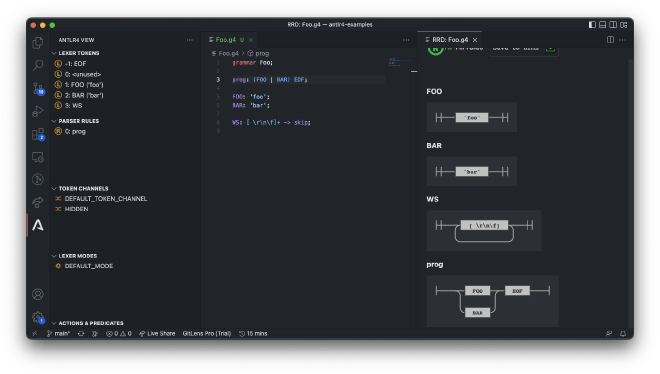

There’s a similar extension called ANTLR4 grammar syntax support for VS Code, and it’s just as powerful. After installing it you get the ANTLR View panel, which automatically lists all of the rules declared in your grammar, along with their priorities.

I find this a bit unusual, but most of the actions you can perform with this tool are not listed in the command pallette, and instead they’re accessible from the right click menu. These include generating railroad diagrams, ATN graphs, call graphs, and even creating valid inputs for the grammar which is just crazy!

It’s also worth noting that the extension is configured by default to generate Java runtimes for all grammar files in a directory called .antlr in the same directory, and I found this a bit odd. Fortunately, you can turn this behavior off by setting the "antlr4.generation.mode": "none" option.

Finally, I was unable to find an arbitrary input pane like the one we get for the IntelliJ one, which may be kind of a dealbreaker.

antlr-tools #

Though in-editor tools are extremely useful, I feel a bit constrained by them, because it means that I have to work with inside an editor and within the scope of a project at all times, but that may not always be the actual case. Sometimes I might just want to open up a terminal, feed some input to some grammar and see its results, and this is where antlr4-tools come in to rescue.

As a JVM project, ANTLR essentially has a JAR file that contains the dependencies for the Java runtime, and can also be run using java -jar antlr4.jar ... to generate runtime codes for various languages, as well as parsing grammars and outputting debug information.

So you could either manually download the JAR file, put it somewhere like /path/to/antlr4.jar so you wouldn’t accidentally delete it, and add an alias alias antlr4="java -jar /path/to/antlr4.jar on your .bashrc or .zshrc to run ANTLR, or you can simply install antlr4-tools which does this automatically for you.

$ pip install antlr4-tools

# if you have distinct executables for Python 3

$ pip3 install antlr4-tools

When you install antlr4-tools you’ll get two executables defined in your PATH variable: antlr4 for generating runtime code for a grammar, and antlr4-parse for simply parsing a grammar and outputting debug information.

To generate runtime for a grammar in Java you can run antlr4 Grammar.g4, and since it’s a light wrapper around the ANTLR JAR file you can pass any argument that the JAR would accept, so you can run antlr4 -Dlanguage=cpp Grammar.g4 to generate runtime in C++

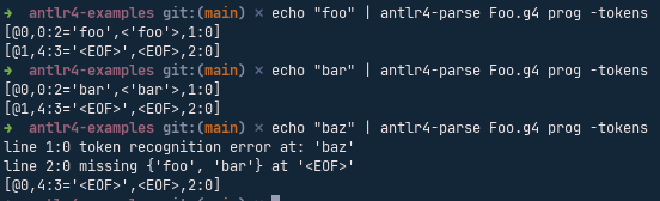

antlr4-parse, on the other hand, accepts source input from stdin in a read mode, but you can also run regular stdin operations to feed your command without the TTL, or from a file.

For instance, the following comands would list the tokens generated by the grammar for the given string

# assume the root rule is `prog`

$ echo "foo" | antlr4-parse Grammar.g4 prog -tokens

$ echo "foo" > source.txt

$ antlr4-parse Grammar.g4 prog -tokens < source.txt

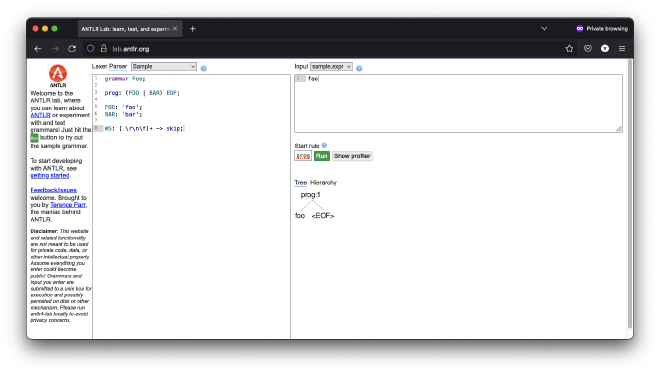

ANTLR Lab #

The in-editor tools are good for being able to see the results immediately without having to run a command, and CLI tool is good for not having to run an editor in the first place.

The ANTLR lab is an online, browser-based editor is very similar to the IntelliJ plugin, and it doesn’t require any editor, so it offers the best of both worlds. It’s not as smooth as the plugin, though, and it does send your grammar and source to a backend so if you’re privacy-concious you might want to avoid the browser version.

In that case you might want to check out the source code and build it yourself: https://github.com/antlr/antlr4-lab

ANTLR Fundamentals #

As mentioned earlier, ANTLR has an EBNF-like syntax for declaring grammars.

Basic Syntax #

- Strings are represented with single quotes, e.g.

'FOO','BAR' - Comments start with a double slash e.g.

// here is some comment - Tokens are declared in UPPERCASE, and parser rules are declared in camelCase, which colons after the names, and a semicolon to terminate the expression

rule: FOO;FOO: 'foo'; - Tokens can be represented with full strings, regular expressions, or a combination of both, eg:

FOO: 'foo';,NUMBER: [0-9]+;,ALPHANUMERIC_STRING: '"' [A-Za-z0-9]+ '"'; // captures “foo42” - Rules can be combined with the pipe operator

|to create union rules, e.g.fooOrBar: foo | bar; - ANTLR has the concept of channels, and tokens can be routed to certain channels via the

->operator. It’s common to use this notation to ignore all kinds of whitespace by routing them to theskipchannel, e.g.WS: [ \r\n\f\t]+ -> skip EOFis a built-in token that specifies the end of input, and is generally used as the last captured token to prevent the parser from going beyond the input. All other token names and rule names are arbitrary, and there’s no set rule on how they should be named

Files and Naming Conventions #

Given an arbitrary language Foo, you can either have a grammar file containing both the lexer and parser rules called Foo.g4, or separate those two into FooLexer.g4 and FooParser.g4 instead.

In the former approach we’re expected to declare our grammar name as grammar Foo; (notice how the casing matches the filename), whereas in the latter we’re expected to declare them with a lexer or parser prefix such as lexer grammar FooLexer;, and also specify the lexer component when declaring the parser using options { tokenVocab = FooLexer; }.

We can also inject arbitrary code into the generated lexer or parser code using @header { ... } or @footer { ... } blocks, the former of which is very helpful for adding package statements to our files.

Finally, it’s important to note that the rules higher up in the list of rules take precedence over the others, so it’s kind of a convention to keep more specific rules at the higher levels while placing more generic ones at lower levels. As such, it’s also very common to list the parser rules at the top and place lexer rules at the bottom of the file.

Basic Example #

So let’s combine everything that we’ve listed and create a grammar that accepts foo or bar as the input.

In a context-free grammar there’s no such thing as magic, so we need to specify every single token that the lexer is going to encounter. So if we want the input to only contain foo or bar, but also want to accept inputs like foo , bar or foo\n, we’ll have to tell ANTLR to ignore whitespaces. Likewise, if we want to stop the parser as soon as the input ends (which we should almost always do), then we’ll need to tell it that EOF is a valid token in our rule.

If we were using regular expressions we would probably use a pattern like ^\s*(foo|bar)\s*$ to capture the tokens from an input.

To parse the same input in the same format in a context-free grammar, however, we would need lexer rules to capture foo or bar, and a parser rule that accepts either tokens and is terminated with an EOF.

So let’s build an ANTLR grammar with those rules:

Foo.g4

grammar Foo;

prog: (FOO | BAR) EOF;

FOO: 'foo';

BAR: 'bar';

WS: [ \r\n\f\t]+ -> skip;

And if we were to separate the lexer and parser rules into different files (which is a total overkill for this example), here’s how it would look:

FooLexer.g4

lexer grammar FooLexer;

FOO: 'foo';

BAR: 'bar';

WS: [ \r\n\f\t]+ -> skip;

FooParser.g4

parser grammar FooParser;

options { tokenVocab = FooLexer; }

prog: (FOO | BAR) EOF;

At this point, you might be thinking that, since whitespaces are being routed to the skip channel, all whitespaces in between non-whitespace characters might also be ignored, so f o o or ba r are also valid inputs, but that is not the case. Though the output of our parser is a tree of tokens which can be traversed laterally, the parsing process itself is linear and tokens are considered atomic, so thankfully, a token such as FOO: 'foo'; can only be matched by literal foo, with no other character in between, even if it’s being ignored.

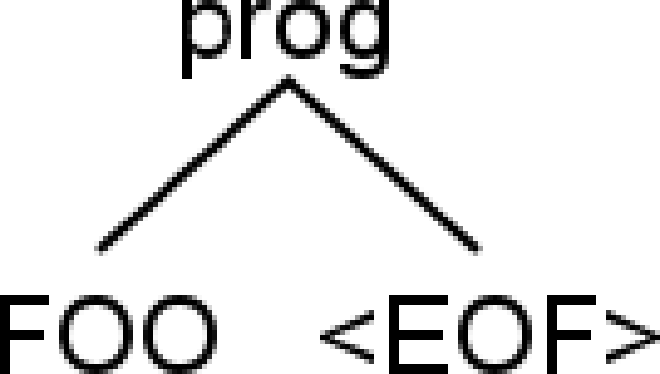

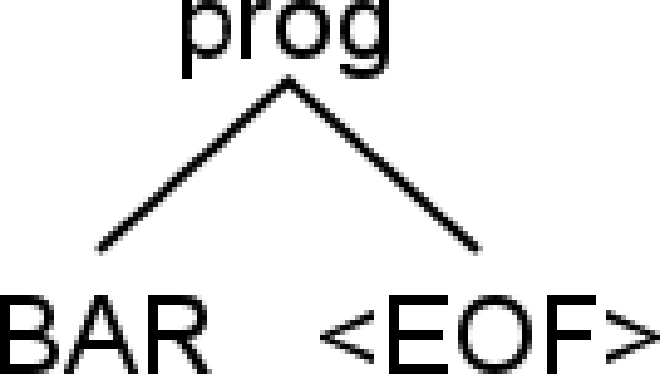

With that affirmation, let’s look at some of the parse results for different inputs.

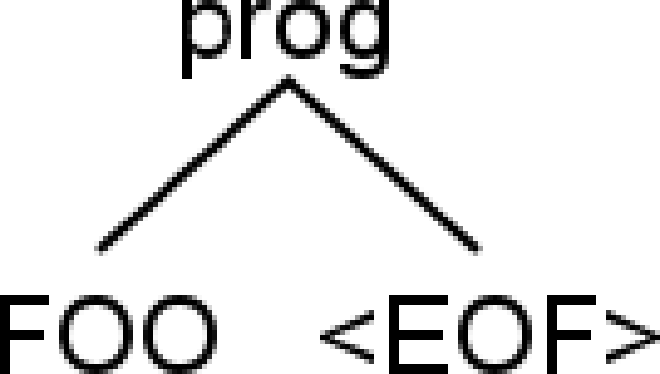

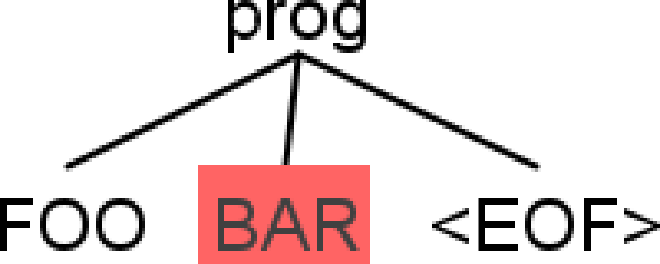

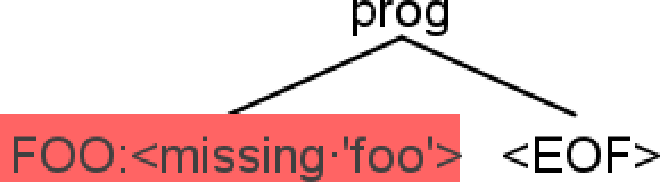

| Input | Valid Source? | Parse Output | Parse Tree |

|---|---|---|---|

foo |

Yes | [@0,0:2=‘foo’,<‘foo’>,1:0] |

|

bar |

Yes | [@0,0:2=‘bar’,<‘bar’>,1:0] |

|

bar |

Yes | [@0,0:2=‘bar’,<‘bar’>,1:0] |

|

foo\n |

Yes | [@0,0:2=‘foo’,<‘foo’>,1:0] |

|

foobar |

No | line 1:3 extraneous input ‘bar’ expecting <EOF> |

|

fo o |

No | line 1:0 token recognition error at: ‘fo ‘ |

|

Parse outputs generated via antlr4-parse, and parse trees by the IntelliJ plugin

Example: Arithmetic Expressions #

The grammar in our previous example was just for show, so now let’s move on to a more concrete example, and create a grammar to parse arithmetic operations.

Multiplication and division obviously have precedence over addition and subtraction, but let’s ignore that for now.

All arithmetic operations are in the form of 1 + 2 so let’s start with the simplest grammar that can parse it

grammar ArithmeticExpression;

expr: NUMBER OP NUMBER EOF;

OP: PLUS | MINUS | DIV | TIMES;

PLUS: '+';

MINUS: '-';

DIV: '/';

TIMES: '*';

NUMBER: [0-9]+;

WS: [ \r\n\f\t] -> skip;

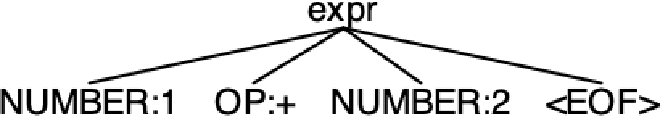

And let’s feed in the expression 1 + 2 into this grammar

$ echo "1 + 2" | antlr4-parse ArithmeticExpression.g4 expr -tokens

[@0,0:0='1',<NUMBER>,1:0]

[@1,2:2='+',<OP>,1:2]

[@2,4:4='2',<NUMBER>,1:4]

[@3,6:5='<EOF>',<EOF>,2:0]

Alright, so we can figure out the operator by looking at OP token, and the left and right numbers by looking at the NUMBERS tokens, but we can do one better and label the left and right tokens which will then help us access these tokens by their name.

Note that this has no effect on the parse output but it does allow the generated runtime code to access the tokens by labels.

grammar ArithmeticExpression;

expr: left=NUMBER OP right=NUMBER EOF;

OP: PLUS | MINUS | DIV | TIMES;

PLUS: '+';

MINUS: '-';

DIV: '/';

TIMES: '*';

NUMBER: [0-9]+;

WS: [ \r\n\f\t] -> skip;

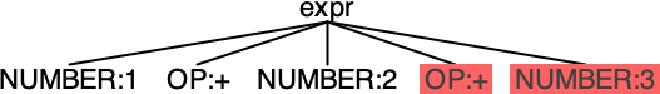

Notice that our parser rule terminates with an EOF token, and it only accepts numbers on its left and right handles, so at this stage it can’t parse inputs such as 1 + 2 + 3

$ echo "1 + 2 + 3" | antlr4-parse ArithmeticExpression.g4 expr -tokens

line 1:6 mismatched input '+' expecting <EOF>

[@0,0:0='1',<NUMBER>,1:0]

[@1,2:2='+',<OP>,1:2]

[@2,4:4='2',<NUMBER>,1:4]

[@3,6:6='+',<OP>,1:6]

[@4,8:8='3',<NUMBER>,1:8]

[@5,10:9='<EOF>',<EOF>,2:0]

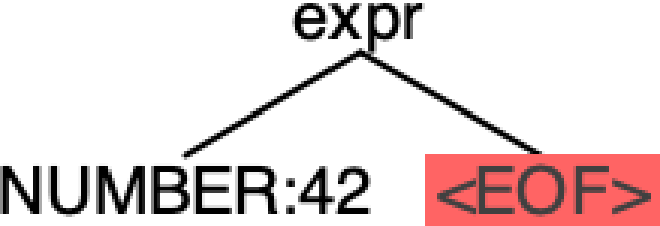

Notice how the IntelliJ plugin also reports errors on the parse tree

Similarly, the grammar only accepts an operation with left and right handles, so it can’t even parse the input 42.

$ echo "42" | antlr4-parse ArithmeticExpression.g4 expr -tokens

line 2:0 mismatched input '<EOF>' expecting OP

[@0,0:1='42',<NUMBER>,1:0]

[@1,3:2='<EOF>',<EOF>,2:0]

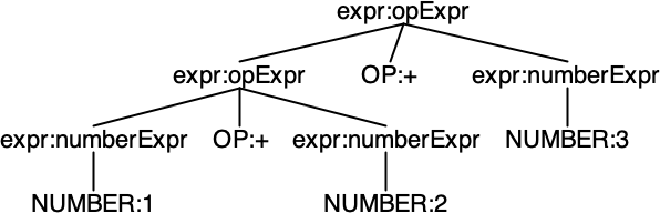

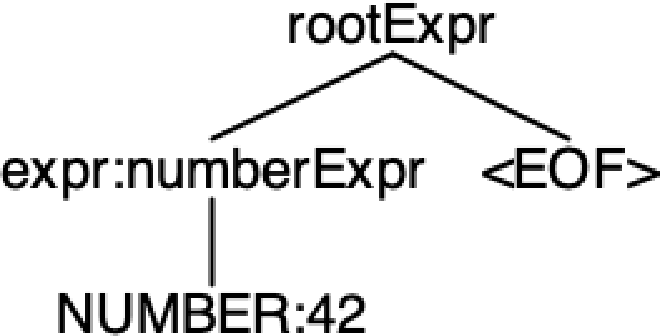

Let’s address both issues by adding a new rule to capture the root, and modify the expr rule to also accept numbers while also labeling the options

grammar ArithmeticExpression;

rootExpr: expr EOF;

expr

: NUMBER #numberExpr

| left=expr OP right=expr #opExpr;

OP: PLUS | MINUS | DIV | TIMES;

PLUS: '+';

MINUS: '-';

DIV: '/';

TIMES: '*';

NUMBER: [0-9]+;

WS: [ \r\n\f\t] -> skip;

For 1 + 2 + 3

$ echo "1 + 2 + 3" | antlr4-parse ArithmeticExpression.g4 expr -tokens

[@0,0:0='1',<NUMBER>,1:0]

[@1,2:2='+',<OP>,1:2]

[@2,4:4='2',<NUMBER>,1:4]

[@3,6:6='+',<OP>,1:6]

[@4,8:8='3',<NUMBER>,1:8]

[@5,10:9='<EOF>',<EOF>,2:0]

And for 42

echo "42" | antlr4-parse ArithmeticExpression.g4 expr -tokens

[@0,0:1='42',<NUMBER>,1:0]

[@1,3:2='<EOF>',<EOF>,2:0]

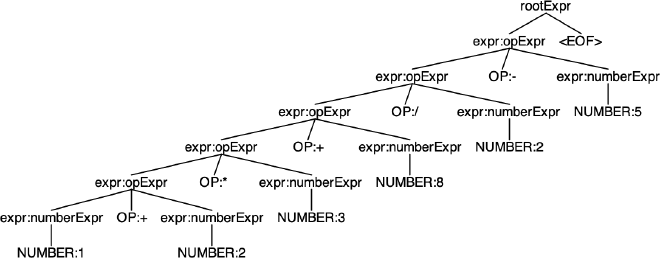

Now let’s feed a longer expression with other operators mixed in, such as 1 + 2 * 3 + 8 / 2 - 5, and look at the parse tree.

Even at first glance things don’t look right because * and / should take precedence over other operators, but they’re not.

Let’s rewrite this expression as a LISP expression and evaluate it from inside out

(- (/ (+ (* (+ 1 2) 3) 8) 2) 5)

(- (/ (+ (* 3 3) 8) 2) 5)

(- (/ (+ 9 8) 2) 5)

(- (/ 17 2) 5)

(- 8.5 5)

3.5

And this is completely wrong, because we should have instead had 6 as the result.

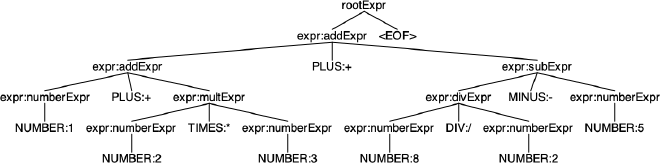

If you recall, rules higher up in the list take precendence over the rest of the rules, and we can take advantage of this to fix the issue.

So let’s get rid of the OP token rule and separate the opExpr into four individual rules for each operations, where all options are labeled.

grammar ArithmeticExpression;

rootExpr: expr EOF;

expr

: NUMBER #numberExpr

| left=expr TIMES right=expr #multExpr

| left=expr DIV right=expr #divExpr

| left=expr MINUS right=expr #subExpr

| left=expr PLUS right=expr #addExpr;

PLUS: '+';

MINUS: '-';

DIV: '/';

TIMES: '*';

NUMBER: [0-9]+;

WS: [ \r\n\f\t] -> skip;

And let’s feed in our expression into this grammar

And there we go, it looks much more accurate! To make sure, let’s rewrite this as a LISP expression and evaluate it like before

(+ (+ 1 (* 2 3)) (- (/ 8 2) 5))

(+ (+ 1 6) (- 4 5))

(+ 7 -1)

6

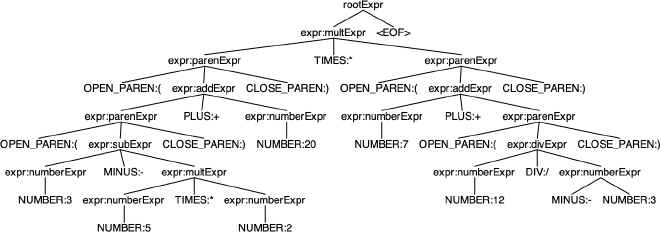

Great! So let’s finish up by adding parenthesis and negative number support so we can parse expressions like ((3 - 5 * 2) + 20) * (7 + (12 / -3)) which would evaluate to 39.

grammar ArithmeticExpression;

rootExpr: expr EOF;

expr

: (MINUS | PLUS)? NUMBER #numberExpr

| OPEN_PAREN expr CLOSE_PAREN #parenExpr

| left=expr TIMES right=expr #multExpr

| left=expr DIV right=expr #divExpr

| left=expr MINUS right=expr #subExpr

| left=expr PLUS right=expr #addExpr;

PLUS: '+';

MINUS: '-';

DIV: '/';

TIMES: '*';

OPEN_PAREN: '(';

CLOSE_PAREN: ')';

NUMBER: [0-9]+;

WS: [ \r\n\f\t] -> skip;

Looks correct, but let’s verify!

(* (+ (- 3 (* 5 2)) 20) (+ 7 (/ 12 -3)))

(* (+ (- 3 10) 20) (+ 7 -4))

(* (+ -7 20) 3)

(* 13 3)

39

Perfect!

Example: HTML Parser #

And now, let’s move on from expressions into a more generalized use case, and implement a simple HTML parser since we’re usually discouraged from using regular expressions to parse HTML, and ANTLR can be a good alternative.

The official ANTLR repo does have a great HTML grammar which has full support for the HTML syntax, but it’d be a nice exercise to write a simpler version of this, just enough to be able to parse the following input:

<h2>Registration Form</h2>

<!-- this form can be used to register to the website -->

<form action="https://some-url.com/some/endpoint" method="POST">

<p>

<label for="email">E-Mail Address:</label>

<input id="email" name="email" placeholder="e.g. [email protected]" />

</p>

<p>

<label for="password">Password:</label>

<input id="password" name="password" type="password" />

<br />

<em>Must contain at least <strong>one uppercase letter</strong>, <strong>one lowercase letter</strong>, <strong>one digit</strong>, and must be <strong>at least 8 characters long</strong></em>

</p>

<p>

<label for="password_confirmation">Password (Confirm):</label>

<input id="password_confirmation" name="password_confirmation" type="password" />

</p>

<button>

Register

</button>

</div>

So let’s start writing our grammar by handling the low hanging fruit that is self-closing elements.

SimpleHtml.g4

grammar SimpleHtml;

doc: element* EOF;

element: selfClosingElement;

selfClosingElement: OPEN tagName=NAME attributes? SLASH_CLOSE;

attributes: attribute (attribute)*;

attribute: name=NAME EQ value=STRING_LITERAL;

OPEN: '<';

CLOSE: '>';

EQ: '=';

SLASH_OPEN: '</';

SLASH_CLOSE: '/>';

NAME: [A-Za-z] [A-Za-z0-9._-]*;

STRING_LITERAL: '"' ~[<"]+ '"';

WS: [ \r\n\t\f]+ -> skip;

With this grammar we can easily parse self-closing elements, even if they span to multiple lines because we’re ignoring whitespaces.

<input id="email" name="email" placeholder="e.g. [email protected]" />

<input id="password" name="password" type="password" />

<br />

<input

id="password_confirmation"

name="password_confirmation"

type="password"

/>

Alright, this looks good enough, so let’s try to add comments and regular elements into the mix.

Since we want the users to be able to put any arbitrary text inside a comment block or an element, we can add a token rule such as TEXT: ~[<]+; and use it in our new parser rules.

grammar SimpleHtml;

doc: element* EOF;

element: selfClosingElement;

selfClosingElement: OPEN tagName=NAME attributes? SLASH_CLOSE;

attributes: attribute (attribute)*;

attribute: name=NAME EQ value=STRING_LITERAL;

OPEN: '<';

CLOSE: '>';

EQ: '=';

SLASH_OPEN: '</';

SLASH_CLOSE: '/>';

NAME: [A-Za-z] [A-Za-z0-9._-]*;

STRING_LITERAL: '"' ~[<"]+ '"';

TEXT: ~[<]+;

WS: [ \r\n\t\f]+ -> skip;

And let’s try to parse the self-closing elements from the previous example

Whoops! It seems like the TEXT token is breaking all our parser rules because it can capture just about anything and override any token captures in our parser rules.

To fix this, we can use ANTLR’s built-in support for parsing modes, which allows tokens to force ANTLR to enter or exit specific modes where only a specific set of token rules are applied.

More specifically, we can put the parser into a mode called IN_TAG when we see < or </ (which means we’re starting to parse a tag), and have it exit the mode when we see > or /> (which means we’ve stopped parsing the tag).

While in the tag parsing mode we can ignore whitespaces, parse attributes in the <name>=<value> form and capture tag closing characters to leave the mode, and while not in the mode we can keep all whitespaces, accept all arbitrary input as TEXT and enter the mode when we see tag opening characters.

To use modes we need to separate our grammar into its lexer and parser components, and then we can use the pushMode(MODE_NAME) and popMode channels (e.g. TOKEN: '...' -> pushMode(MODE_NAME);) in our lexer rules to enter and exit said modes. To specify which tokens should be captured inside a mode we can putting all relevant tokens below the line mode MODE_NAME;, and everything on top will only be captured when not inside the mode.

With that let’s restructure our grammar, add in our modes, and add the final rule to accept block elements.

SimpleHtmlLexer.g4

lexer grammar SimpleHtmlLexer;

OPEN: '<' -> pushMode(IN_TAG);

SLASH_OPEN: '</' -> pushMode(IN_TAG);

COMMENT: '<!--' TEXT '-->';

WS: [ \r\n\t\f]+;

TEXT: ~[<]+;

mode IN_TAG;

CLOSE: '>' -> popMode;

SLASH_CLOSE: '/>' -> popMode;

WS_IN: [ \r\n\t\f]+ -> skip;

EQ: '=';

NAME: [A-Za-z] [A-Za-z0-9._-]*;

STRING_LITERAL: '"' ~[<"]+ '"';

SimpleHtmlParser.g4

parser grammar SimpleHtmlParser;

options { tokenVocab = SimpleHtmlLexer; }

doc: (WS* element WS*)* EOF;

element: (selfClosingElement | blockElement | comment);

selfClosingElement: OPEN tagName=NAME attributes? SLASH_CLOSE;

blockElement

: OPEN tagName=NAME attributes? CLOSE

WS*

blockContent?

WS*

SLASH_OPEN closingTagName=NAME CLOSE;

blockContent: (text=TEXT | element) (WS* blockContent)*;

comment: COMMENT;

attributes: attribute (attribute)*;

attribute: name=NAME EQ value=STRING_LITERAL;

As you can see we now have to consider the dangling whitespaces in between the tags because we can’t ignore them when we’re not parsing the tag (e.g. not in IN_TAG mode), and that we’re also capturing comments as a full token because otherwise we wouldn’t be able to terminate the TEXT token with --> using a parser rule.

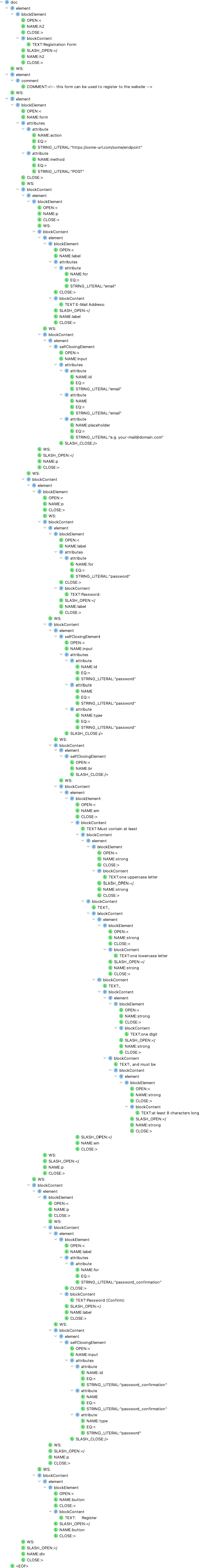

Since we can now handle all use cases let’s feed in our entire HTML and let’s see how the parse tree looks.

It might be difficult to see the whole tree so here it is in another form (which is slightly better at best):

Oh wow, that’s a long (tall?) tree, but at least it’s correct.

Conclusion #

As you can see, ANTLR is a great tool for parsing just about any kind of input, and it’s pretty straightforward to use.

For me its biggest downside is that it’s primarily a JVM tool first, so it kinda locks you in to the Java ecosystem, but in today’s world with microservice-based systems and powerful FFI systems it might be a negligible issue.

Anyways, so far we’ve just been able to parse an input and didn’t even get to add semantic validation on top of it (i.e. the input <foo>42</bar> is syntactically correct but not semanticaly), let alone execute, evaluate or process the tree.

In the next article we’ll exactly be doing that, so stay tuned!